How can you read a haiku?

On the difficulties of typesetting small poetic forms from other languages

News and Sundry

This Saturday, 9/13, at 6:30 PM, there will be an event called “Poetry in Place” happening at Lot 49 books in Fishtown, Philadelphia, “a reading, conversation, and launch…for those interested in the geography of poetry.” It will feature local—and excellent—writers Audrey Lee and Graham Irvin, as well as Noam Hessler, who is reading from their poetry collection Officeparks, out now through Farthest Heaven.

Next week, there will be two talks on esoteric Pennsylvania history given by Timothy Grieve-Carlson, Assistant Professor of Religion at Westminster College. The first will be on the 17th, about 17th-century mystic Johannes Kelpius, held at the Valley Green Inn in beautiful Wissahickon Park in Philadelphia. The second talk will be about an early account of poltergeists in America, held at the historic Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster County.

New Directions has just announced their Winter 2026 catalog. Among their new releases is The Complete Works of Ricardo Reis, volume three in their Fernando Pessoa heteronyms series. Instead of one authorial voice, Pessoa had many, with Reis being the conservative classicist. From the catalog: “Ricardo Reis was imagined as a melancholic doctor ‘with a darkish complexion,’ a self-taught Hellenist who exiled himself in Brazil because he was a monarchist. In a 1914 letter to Pessoa, the writer Mário Sá-Carneiro described Reis’s odes as ‘admirable,’ ‘a marvel of impersonality,’ praising the way he ‘achieved a Horatian, classical novelty.’” Come to think of it, a volume of Sá-Carneiro translations would be welcome too.

Poetry and Legibility

Responsibilities multiply themselves. I’m still working on that longer piece about LLM-based translation services, but my role as publisher, or rather, my role as very small publisher, who’s in charge of everything from editing to cover design, also comes with pressing duties. I’m still typesetting Shadowings by Lafcadio Hearn, and have led myself into a tight spot—poetry.

English-language readers have been steadily familiarized with Japanese traditional forms—haiku, tanka, and so on—for almost a hundred and fifty years. They just don’t seem all that new or radical to us. But at the turn of the 20th-century, when Hearn was first publishing his accounts of Japanese culture, they certainly were. They must have sounded so terse, so abrupt, compared to the logorrheic conventions of Euro-American poetry at the time. But part of that unfamiliarity must have been also the odd context in which Hearn presented this radically new poetry, in a chapter about Japanese folk beliefs about cicadas.

While for some this anthropological data might suggest a dusty textbook survey, Hearn’s essay, at least for me, is anything but that. This is apparent from the first few paragraphs, in which Hearn reveals that the Chinese and Japanese believed that cicadas didn’t eat food, but rather sustained themselves on dew, a characteristic which made the insects moral exemplars.

A celebrated Chinese scholar, known in Japanese literature as Riku-Un, wrote the following quaint account of the Five Virtues of the Cicada:—

“I.—The Cicada has upon its head certain figures or signs. These represent its [written] characters, style, literature.

“II.—It eats nothing belonging to earth, and drinks only dew. This proves its cleanliness, purity, propriety.

“III.—It always appears at a certain fixed time. This proves its fidelity, sincerity, truthfulness.

“IV.—It will not accept wheat or rice. This proves its probity, uprightness, honesty.

“V.—It does not make for itself any nest to live in. This proves its frugality, thrift, economy.”

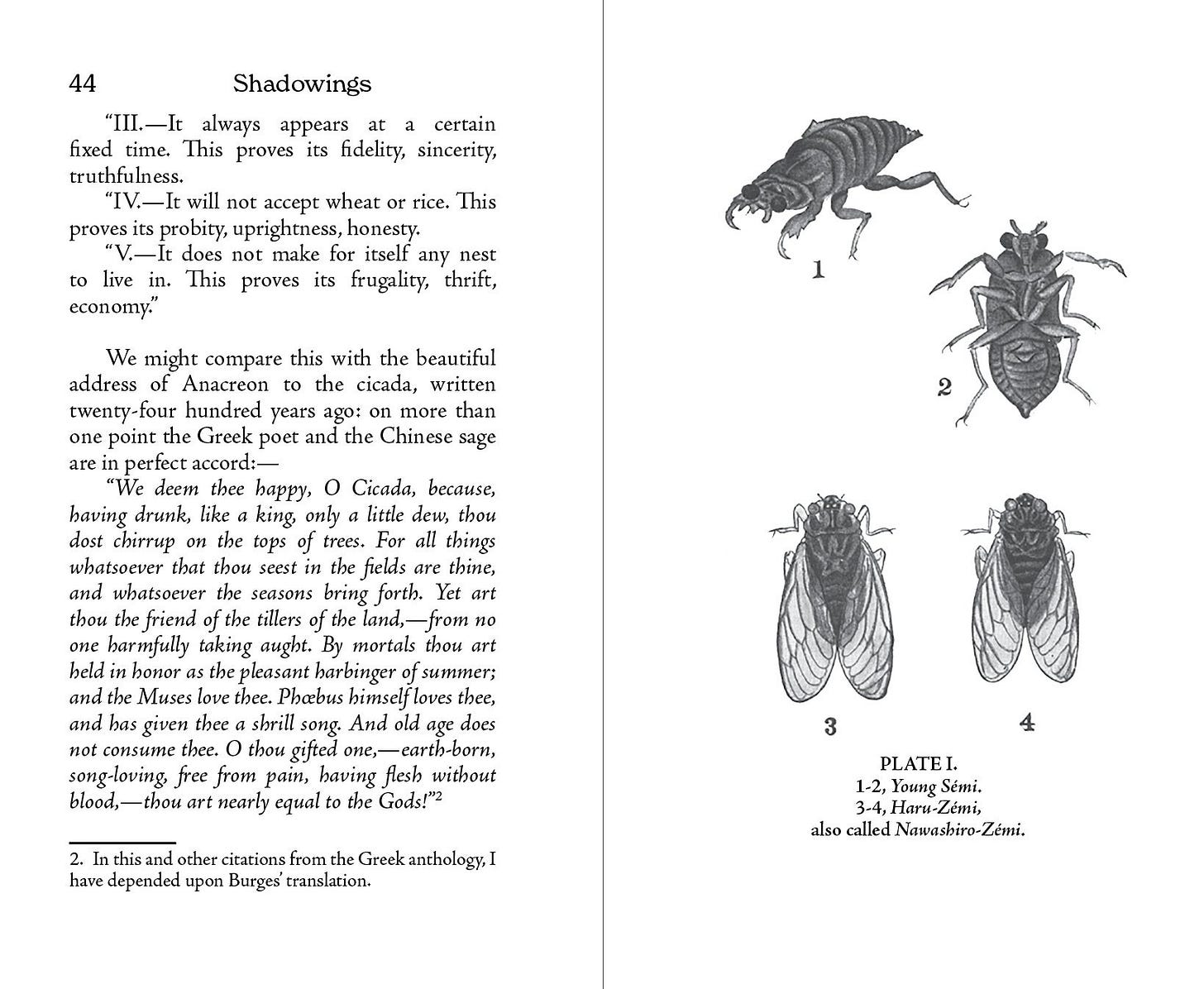

Hearn goes on, enumerating more of these quaint properties. The Japanese had—perhaps they still have, I’m no expert—a rather elaborate folk taxonomy for the different cicada species. These include the aburazémi, so named, Hearn tells us, because “its shrilling resembles the sound of oil or grease frying in a pan.” That sounds quite fanciful, a product of a culture obsessed with food, or perhaps not; Smithsonian Magazine states that there are over 3400 species of the insect. Odds are that there are some really weird-sounding ones—well, weirder than usual.

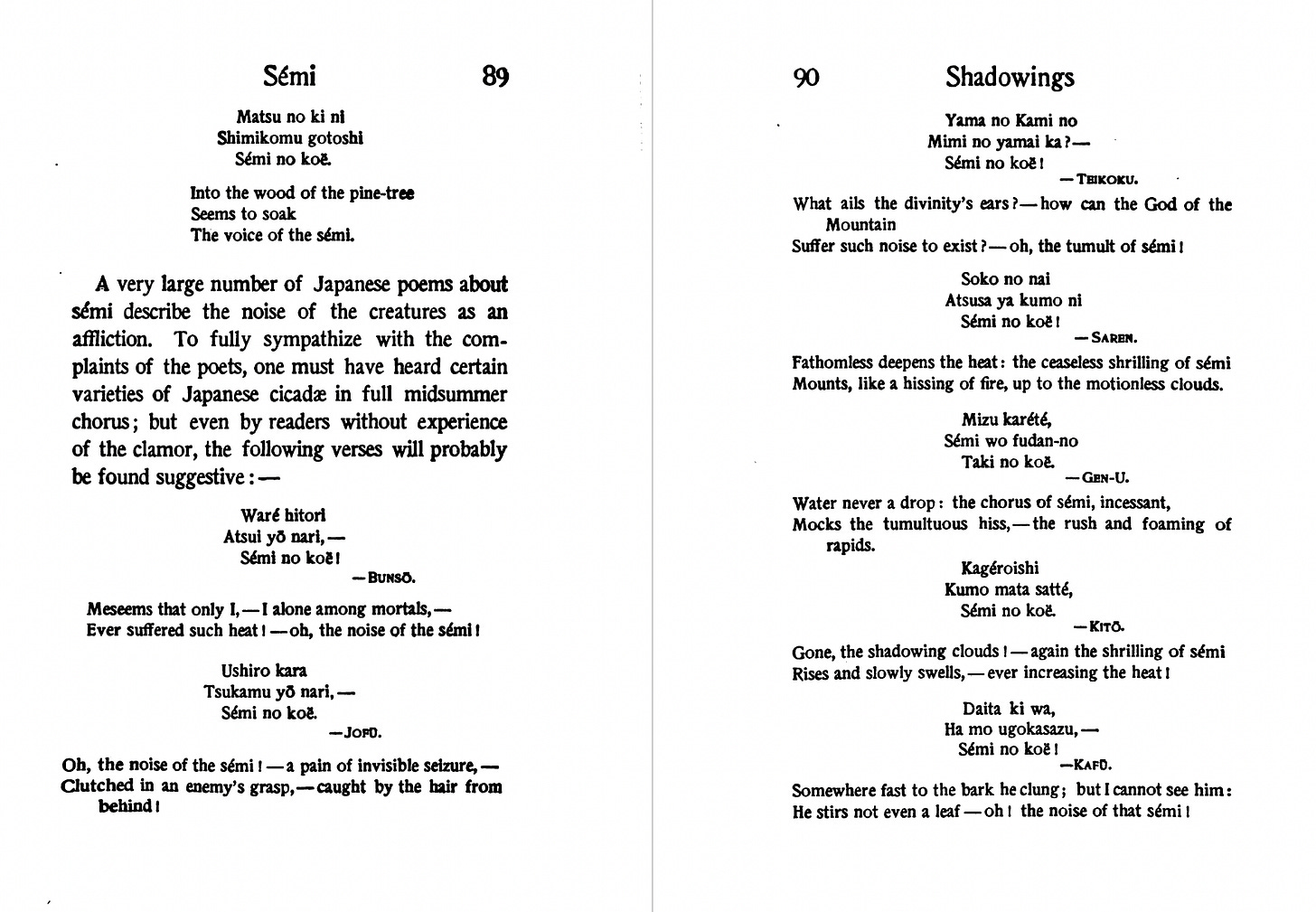

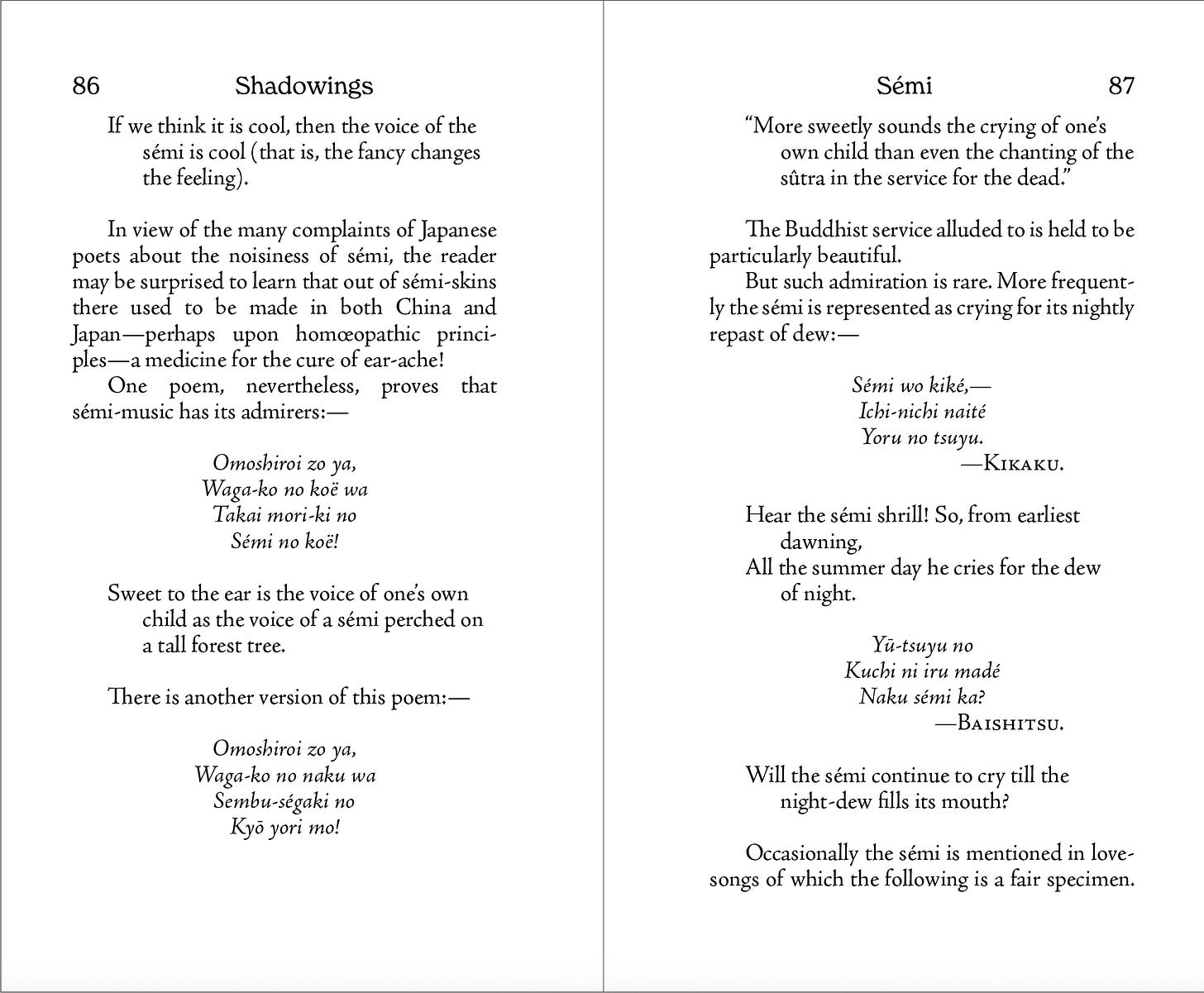

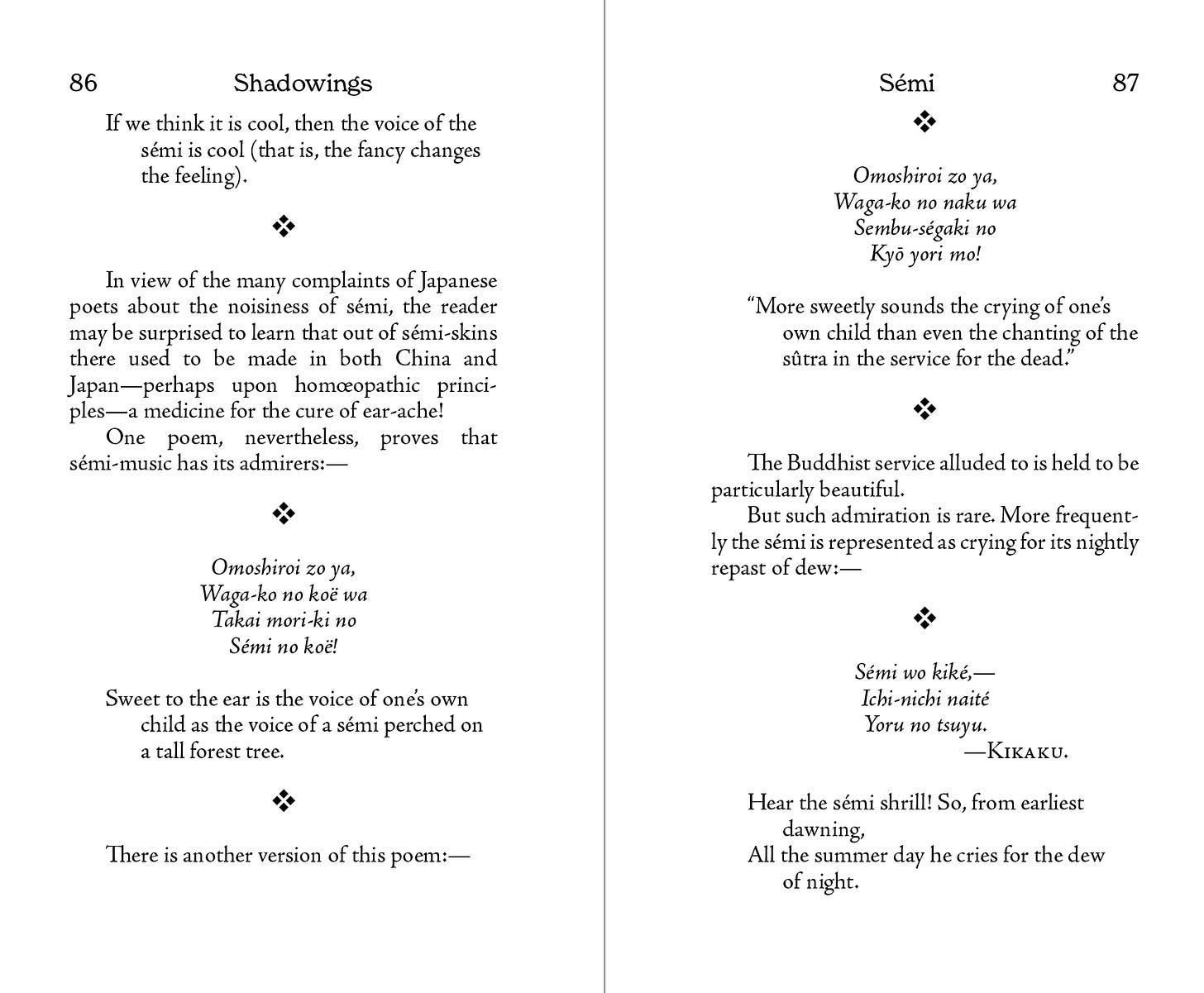

If the chapter consisted of just charming trivia about cicadas, I wouldn’t be having such a difficult time. Instead, near the end, the reader, and by extension the typesetter, is confronted with poem after poem about cicadas, without much in the way of headings to differentiate them. The original typesetter put the English translations in a different font size, which helps a little with legibility, but it never quite creates a sense of separation necessary to read each poem as a separate piece, discrete from the others:

But this legibility problem, which was mild in original, compounded itself when I set my own layout of the text. I wanted to keep the fonts the same (relatively large) size, but that ended up making the poems more difficult to read.

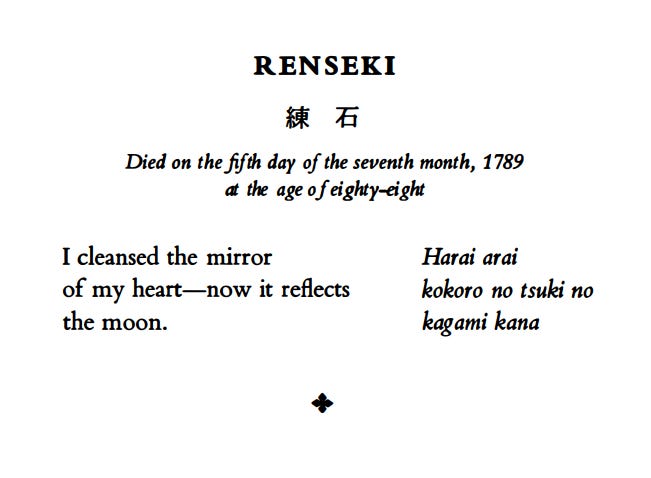

Adding italics, used elsewhere for passages in Japanese, helped somewhat, but I needed something extra. With luck, I had my copy of Japanese Death Poems in reach, an anthology of jisei, a type of traditional poem composed just before death. Edited by Yoel Hoffmann, this anthology was one of the first books that got me into Japanese literature. Consulting it again, I was struck about how clear the layout was, how easily it broke down what could have otherwise been a jumble of material.

At that point, I really wished I knew Japanese better; I could have supplied the names of the poets in kanji characters, as Hoffmann does, but such a task wasn’t in the remit for this book. None were supplied in the original publication, nor could they have been in all probability. I doubt any English-language press could have printed them, at least none outside of Japan or in select cities along the West Coast of the United States.

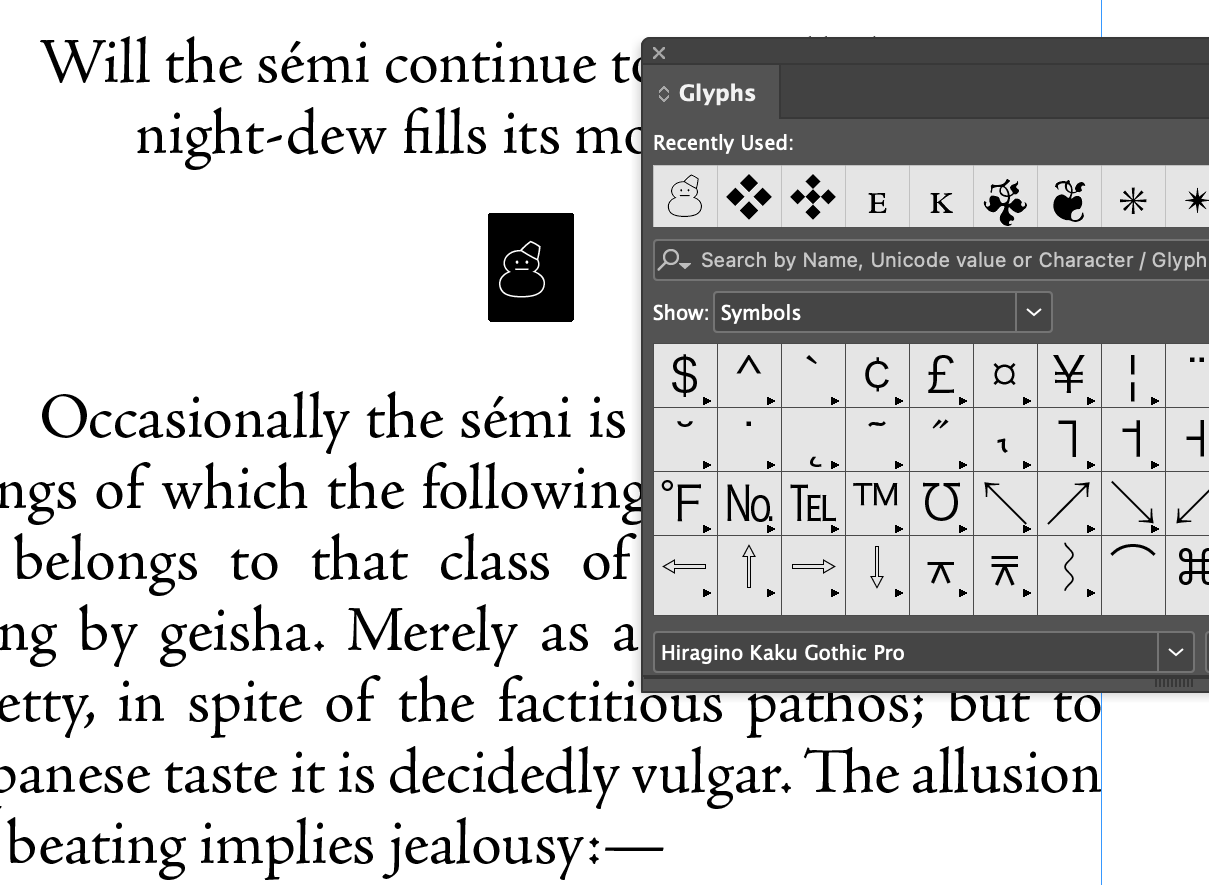

Since I was dealing with a much narrower page—I won’t bore you with the dimensions—I decided not to split the Japanese and the English versions of the poems into their own separate columns. I did, however, separate each entry with a diamond pattern (❖), its function similar to an asterism or a dinkus, typographical oddities that I’ve talked about before. I felt these insertions made a big positive difference in organizing the text.

This is all provisional work. Until the book goes to print, I reserve the right—the obligation, really—to continue improving the layout of the book. But I’m hesitant to erase the work I did for this chapter. It was quite the pain in the ass to find a font in Adobe Creative Suite that had the ❖ symbol. I had cycle through dozens of examples before one could display—it was a Japanese font, as it turned out: Hiragino Kaku Gothic.

Having four different writing systems and thousands of characters spread between them, the Japanese have a large inventory of symbols that the typographer can play around with. In certain Japanese fonts, Hiragino Kaku Gothic, for instance, the Unicode symbol for snowman wears an amusingly bland expression on his face and, randomly enough, a fez on his head. I really wish I could just type that snowman whenever I want; it’s so much more distinctive than the emoji that’s rendered when the symbol is displayed on a Mac: ☃. What will I used the fez-snowman for? I haven’t got a clue. But someday, it’ll be quite handy—someday, eventually. I know it. I’m sure.