The Beautiful Dinkus

Some undisciplined thoughts about personal health, Lafcadio Hearn, and obscure typographical marks

I seem to be recovering from the bout of kidney stones I had last week, recovering well enough, that is, since at least I’m not suffering any acute pain from them. I’ve always had poor to mediocre health, even as a teenager, and going back to the Pacific Northwest tends to bring me down to that same old level. The last time I was out in the Golden West, in March, I got a bad case of the flu, the symptoms of which manifested while I was driving through the Columbia River Gorge, an area of exceptional scenic beauty—old growth timber and three active volcanoes—beauty which is still present but maybe not as appreciable when you’re pulled over on the side of the highway and vomiting into a ditch. But these health complaints, which become tedious even to the complainer, are behind me, for the moment at least; I’m leaving soon for Philadelphia and its salubrious wet-bulb climate. Pennsylvania does wonders for the health.

Meanwhile, I’ve been typesetting Lafcadio Hearn’s Shadowings, a very unusual book, even for this very usual author. Born in 1850 in Greece to a Greek mother and an Irish father, Hearn began his career as a journalist in the American Midwest and South. He was one of the first writers to document Creole cooking and Louisiana Voodoo. He was also a translator of French symbolist literature, including Theophile Gautier and Guy de Maupassant.

If readers know Hearn today, they know of him through his writings about Japan. The author spent the last 14 years of his life there, from 1890 to 1904, and wrote popular adaptations of native folklore and legends for a Western audience. Hearn remains better known in his adopted homeland than anywhere else. In 1964, four of his stories were adapted into an anthology horror movie, Kwaidan, by the great director Masaki Kobayashi.

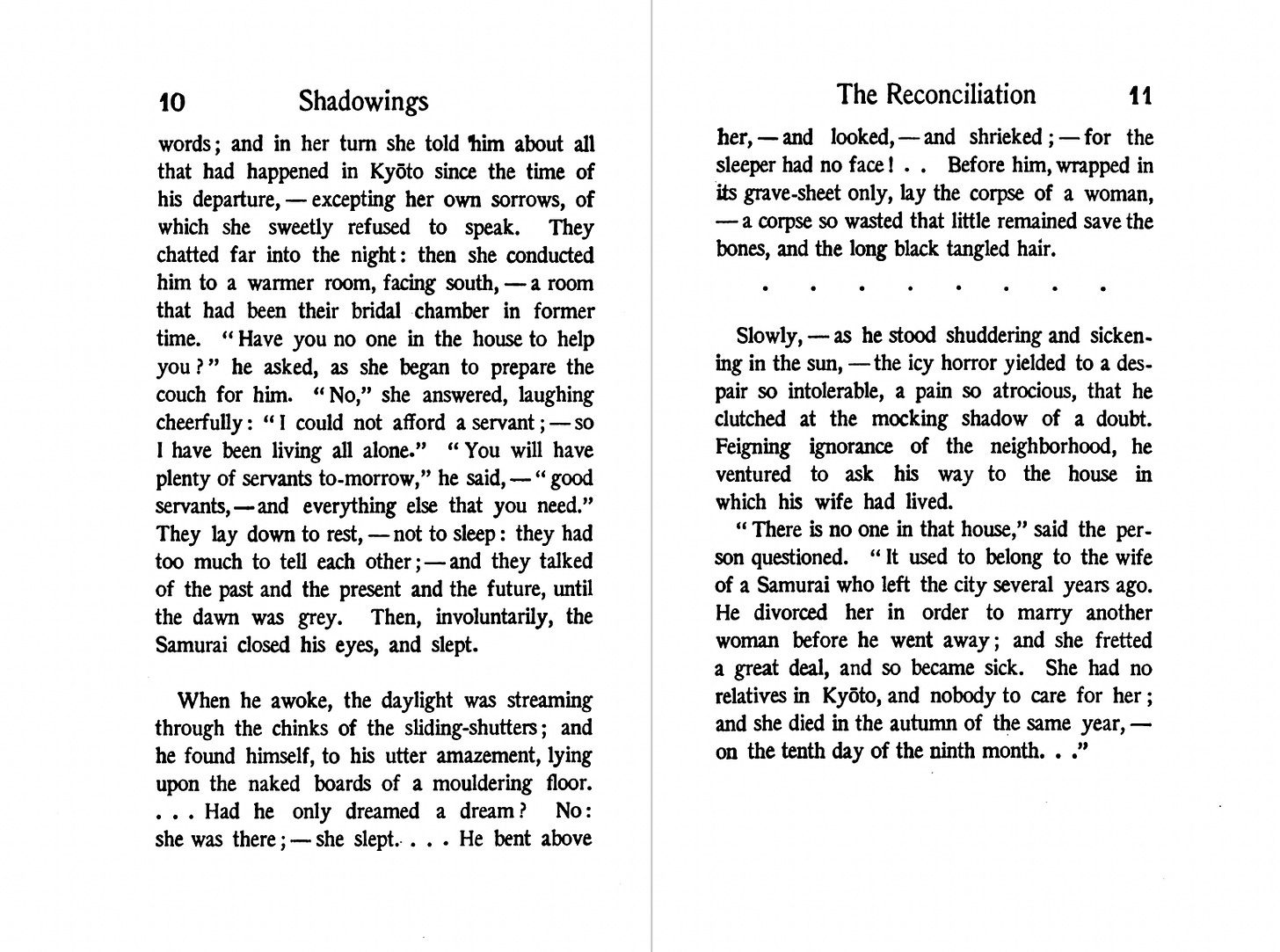

Shadowings contains some of Hearn’s best known material. “The Black Hair” section of Kwaidan, about a jilted wife of a samurai who takes supernatural revenge on her husband, is adapted from “The Reconciliation”, which opens the collection. Nevertheless, Shadowings hasn’t had a high quality reprint in over 50 years.

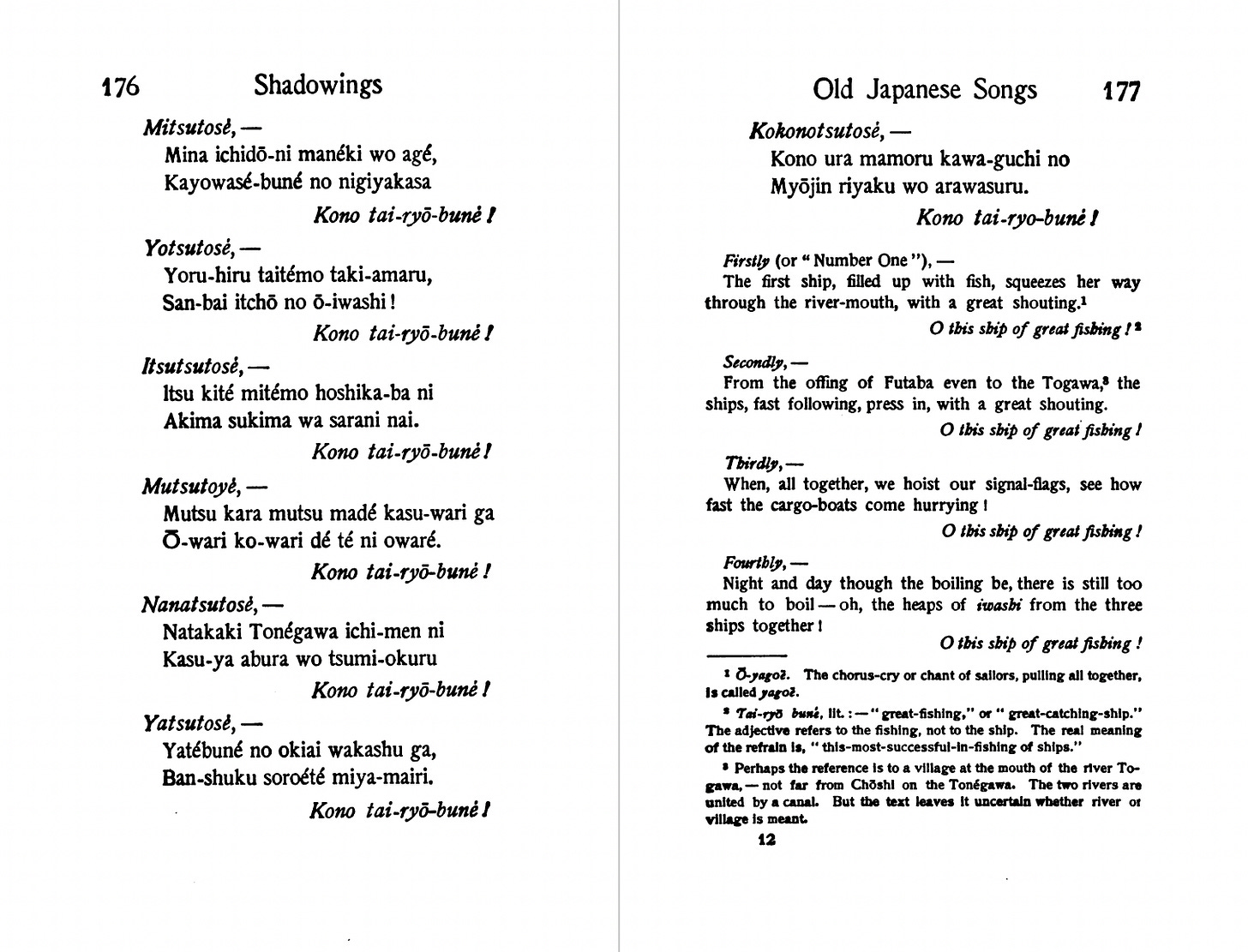

This is probably due to some of the more idiosyncratic qualities of the book: Along with his usual tales of ghosts and goblins, Hearn includes a large collection of folk songs as well as academic essays on Japanese naming conventions and the importance of the cicada to Japanese culture. Also in the mix are much more personal writings, fantasia, as Hearn calls them, hallucinatory autobiographical sketches that would not be out of place, stylistically speaking, in collection by Gautier or Maupassant.

Along with its the idiosyncratic subject matter, Shadowings is also a difficult and ideosycatic book to typeset, with its photographic plates, huge tables of names, and serial quotations from Japanese poets. Even in its less schematic, more narrative sections the typography is complex by bland contemporary standards. Consider the use of the dinkus (∗ ∗ ∗)—that’s the name for a series of dots or asterisks denoting a minor section break.

I’m not well versed in the textual history of Hearn’s work—if that’s documented at all—and don’t know whether the use of such marks was his decision or the decision of others. Regardless, I’ll respect the dinkus—(I’m not above amusing myself with the word: dinkus). It forms part of a varied and expressive inventory of punctuation and typographical devices that contemporary book design chronically neglects . Whether it’s classic literature from the 18th-, 19th-, or early 20th century, contemporary reprints often simplify the punctuation and erase the typography altogether, practices that are even more tragic considering how software has made typesetting radically less difficult and time-consuming.

I consider it my duty as an editor and typesetter to present Hearn’s work as close as possible to what a reader of his era would experience, all while making the necessary concessions when the layout is erratic or difficult to read. I will let others judge whether I’ve succeeded, but the exercise is fulfilling in of itself, a requisite for doing this kind of work, since readers rarely notice details in book design unless they fail in some catastrophic way. Recognition is overrated. It’s not a bad outcome at all if the labor remains invisible.

Part of what motivates me to retain the rarer typographical marks in Hearn’s work, along with the preservationist impulse, is how well these marks match up with the content of the stories. Whoever put them there—whether that was Hearn, his editor, or the book designer—they often have a clear ironic intent, especially when it comes to sex. Uncharacteristic for a male writer of his era, Hearn was frank and unsparing about hypocrisy in that regard. Many of the tales in Shadowings and elsewhere revolve around women who are betrayed by their husbands and lovers. A more straightforward translation or retelling might romanticize the suffering of these women, but Hearn actively intervenes, questioning the ethical grounding of the stories.

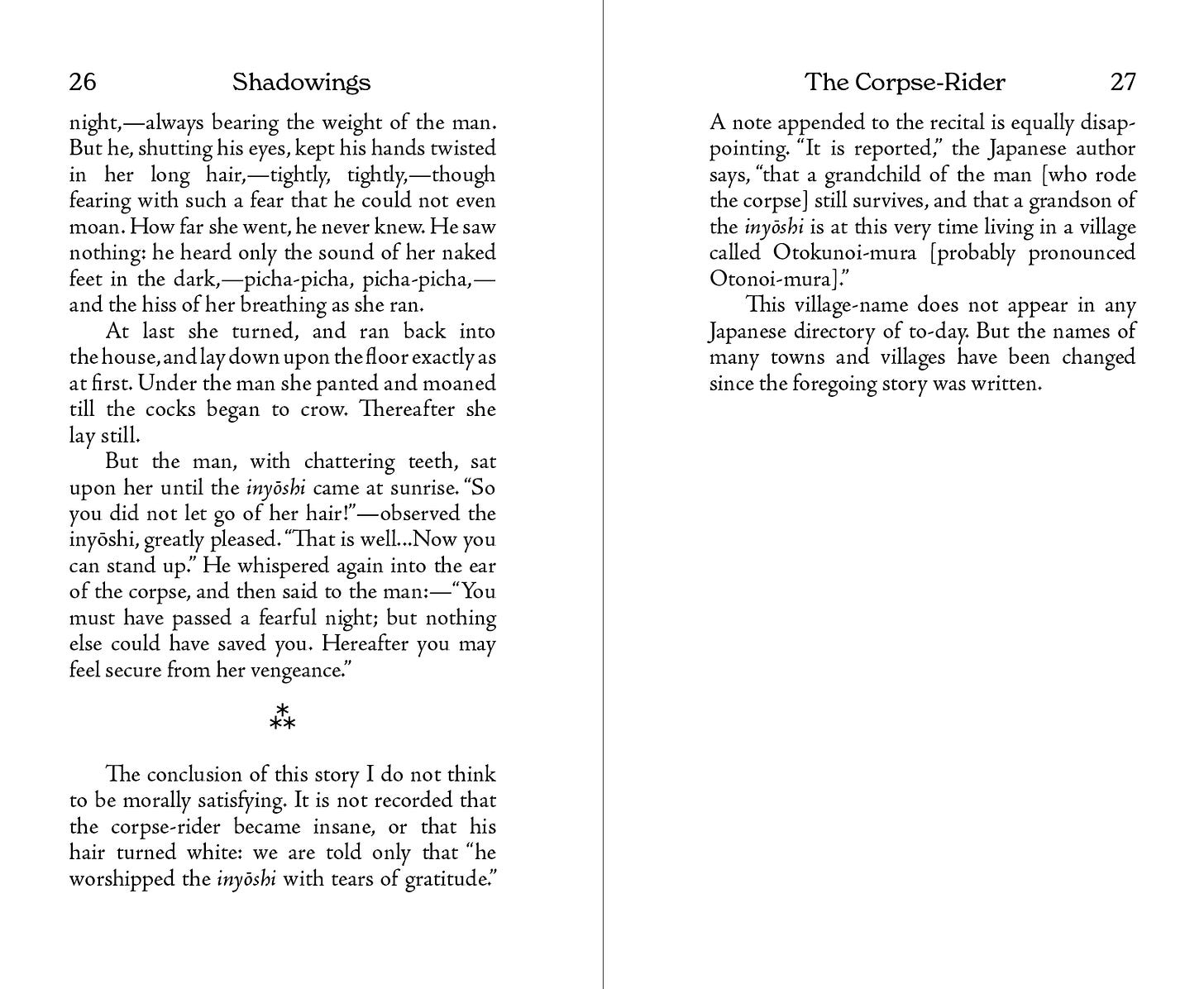

This criticism is particularly sharp and humorous in “Corpse-Rider”, a gruesome tale in which a practitioner of Chinese traditional medicine advises an unfaithful husband, who fears being killed by dead wife’s vengeful spirit, to ride atop her reanimated corpse until sunrise. He succeeds and survives, at least according to legend, and this elicits an amusing mixture of outrage and pedantry from Hearn:

The conclusion of this story I do not think to be morally satisfying. It is not recorded that the corpse-rider became insane, or that his hair turned white: we are told only that “he worshipped the inyōshi [the Chinese medicine practitioner] with tears of gratitude.” A note appended to the recital is equally disappointing. “It is reported,” the Japanese author says, “that a grandchild of the man [who rode the corpse] still survives, and that a grandson of the inyōshi is at this very time living in a village called Otokunoi-mura [probably pronounced Otonoi-mura].”

This village-name does not appear in any Japanese directory of to-day. But the names of many towns and villages have been changed since the foregoing story was written.

This section is marked by another fascinating device, the asterism (⁂), a cluster of three asterisks that has the same function as a dinkus. From a print production standpoint, the variation is an inconvenience. Unicode, an encoding standard that allows the display of those rare characters, is not supported in Adobe Creative Suite, the graphic design software that I use. Very few fonts support them also, and I have to wade through the morass of program support pages and professional forums to find what I need—that or paste an asterism as a vector image, a task that comes with its own set of obstacles.

In the end, I was able to find a dinkus and an asterism that I liked. With the preliminary work done, I can lay out the book in ernest, which is very satisfying, like racing downhill on a bicycle. Nevertheless, I always get a sense of whiplash whenever I get back to work after having a bout of bad health. I feel as though I’ve been slacking—maybe I have. You can luxuriate in pain as well as in pleasure. But you can also luxuriate in persnickety details. They’re the pharmakon that binds together all those poorly set, loosely knitted words.