Did I Exist?

On Kiyoshi Kurosawa's License to Live

There are still a few handmade copies of Phoretics—Israel Bonilla’s pamphlet on the works of Goethe, Emerson, and Hazlitt—available at the Paradise Editions webstore. If you’re interested in literary influence and the incorporation of art into life, or life in to art, then I highly recommend you get a copy or read the essays individually over at Israel’s blog.

David C. Porter, who edits the wonderful journal KEEP PLANNING, has released NTTN, a debut novel through Organ Bank, a small press devoted to transgressive comics and literature. From their website: “NTTN follows two investigators as they listlessly attempt to solve a rash of brutal crimes, using an ominous closed-circuit television station as their North Star.”

Incidentally, KEEP PLANNING has recently published three poems by Israel, which you can read here. “Being of another being, to another, for another, advent of time replenished. Toward the fullness of circumlocution, implacable, tend the roots.” Lovely.

License to Live

It was an inauspicious week to visit New York. Last Monday, near-record rainfall flooded the streets and subways, and, in the suburbs of New Jersey, caused the death of two motorists when their car was swept away into a brook. By the time I arrived in the city on Thursday, for the Japan Cuts 2025 film festival, the torrential rainfall had abated, giving way to the tropical heat and humidity that has become typical of summers along the East Coast. Japan and the United States are an interesting and somewhat depressing contrast in that regard. From 1992 to 2006, the city of Tokyo undertook a massive floodwater diversion project—the largest in the world. I got to see that infrastructure in action during the fall of 2019, just before the Covid pandemic, when I accompanied my girlfriend on a business trip to Ginza, central Tokyo, just in time for a typhoon to roll over Japan. It was amazing to see, despite the torrential rain, how the ground-level buildings stayed dry; amazing, moreover, to see how inner-city life continued in a more or less orderly fashion—it was possible to visit 7-11 and buy a fried chicken sandwich. Contrast that baseline functionality with the widespread devastation and loss of life that accompanies any similar weather event in the United States, a nation that is, at least on paper, significantly wealthier—spectacularly wealthier in the case of Midtown Manhattan (a nearly exact analog to Ginza), where the Japan Cuts 2025 festival took place.

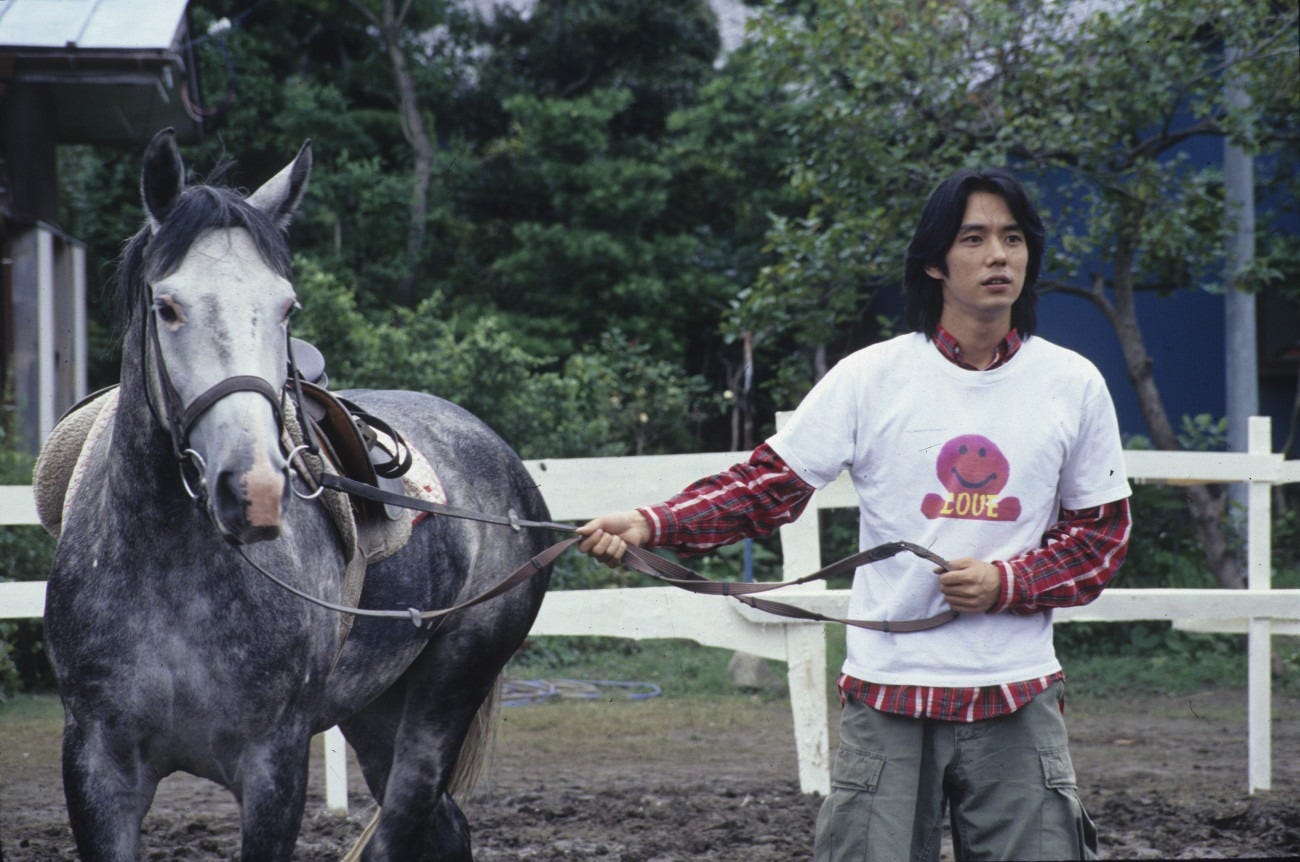

I had come to New York to see a live question-and-answer session with the horror director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, which was to accompany a screening of Serpent’s Path, one of three films, along with Chime and Cloud, that he released last year. Kurosawa’s appearance was cancelled for unspecified reasons, and so, as compensation, I was given tickets for another screening offered by the Japan Center, the organization hosting the festival. I chose the film immediately following Serpent’s Path, another by Kurosawa—a rarely seen comedy from 1998, License to Live. Twenty-four-year-old Yutaka Yoshii, played by Drive My Car actor Hidetoshi Nishijima in his first starring role, wakes up in the hospital from a decade-long coma and has to resume his life as a young man entering into maturity. This is no easy task. In the interim, his mother and father have divorced, and his sister has embarked on a desultory career as a nightclub singer, which leaves Yutaka to rely on a family friend, Koji, who runs a fish farm on the family property. As Yoshii rebuilds his life, he becomes obsessed with reopening a pony farm that once existed there. He finds a runaway horse and starts raising it, charging visitors for rides. The old business revives, family and friends return and reconcile—or at least they reconcile somewhat—but Yoshii’s old injuries, from a hit-and-run accident that left him in the coma, also reassert themselves, threatening to end the whole enterprise.

Having never seen any of Kurosawa’s realist films before, I was interested to see how many of his stylistic trademarks would carry over from his genre work. Quite a few, it turns out, including long, tension-filled cuts of figures looming in the shadows or hurrying through maze-like interiors. And there are thematic as well as cinematographic similarities. Even though Kurosawa frequently includes fantastic elements in his films, these always take place in what we could consider a naturalistic universe. Ghosts, for example, though frightening, are as real as butter or Tuesdays. Nothing exists but what is shown, or what can be shown, on screen. Metaphysics just doesn’t come into it. At the end of License to Live, Yoshii, sensing that his second chance is coming to an end, asks Koji whether he ever existed at all. The answer is affirmative, and therein lies the tragedy, since that existence has now run its course. This palpable sense of mortality and transience—this sense of the fragility of life and the nearness of death—gives Kurosawa’s films a weightiness that cuts against, and works with, the fantastical elements within them. You laugh and you grimace because what happens can never be undone. Nothing returns, nothing repeats, because everything is real. For that reason, Kurosawa is one of the most compelling filmmakers working today.