Stepping Outside the Brackets

On David Jones and Kiyoshi Kurosawa

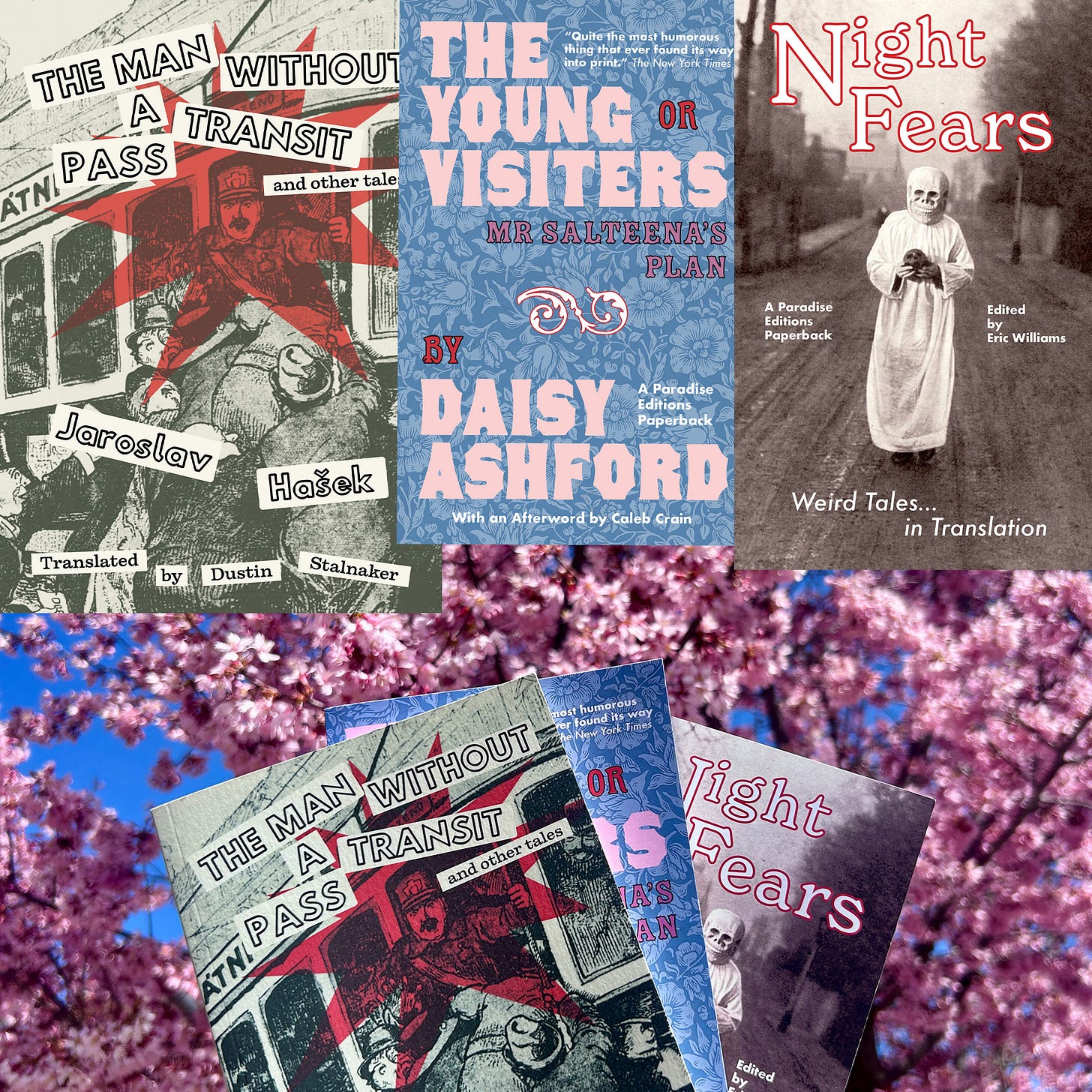

First an announcement: my small press, Paradise Editions, is offering a spring bundle of its first three titles: The Man Without a Transit Pass by Jaroslav Hašek (trans. Dustin Stalnaker); Night Fears: Weird Tales in Translation, edited by Eric Williams; and finally, The Young Visiters by Daisy Ashford. $29 for the lot of them. They can be purchased here. Individual titles are also offered at a discount.

If you’d like to support the press in other ways, please also consider becoming a paying subscriber to this newsletter, as the money generated by that goes towards web-hosting and printing costs for the press.

In Parenthesis by David Jones

The title is enigmatic, and reading through this long poem (or novel in verse) about the First World War, you still wouldn’t know why it’s called In Parenthesis. An explanation lies outside the text proper, in the preface, where Jones lays out, with a kind of tragic detachment, how his experience as a common soldier defined the scope of the work. The poem takes place between December 1915, when Jones left for the Western Front in France, and July 1916, when the conduct of the war deteriorated.

From then onward things hardened into a more relentless, mechanical affair, took on a more sinister aspect. The wholesale slaughter of our later years, the conscripted levies filling the gaps in every file of four, knocked the bottom out of the intimate, continuing, domestic life of small contingents of men, within whose structure Roland could find, and, for a reasonable while, enjoy his Oliver. In the earlier months there was a certain attractive amateurishness, and elbow room for idiosyncrasy that connected one with a less exacting past.

This is the parenthesis that Jones writes of—“how glad we were to step outside its brackets”—a war that was, at least at first, shot through with knightly romance, the amor present in “amateur” present in its many forms. Jones loved soldiering, loved the companionship of his fellow soldiers, until the war annihilated them and came close to annihilating him. He served longer on the front lines—117 weeks—than any other British writer. He did not publish the poem until 1937, when another catastrophic war threatened; “Tardy” T.S. Elliot called Jones, with his usual schoolmaster affect, but still counted the Welshman among his peers.

As shown by Roland and Oliver, Jones’ references are antique and erudite, requiring the extensive endnotes that he helpfully provides. He draws not only from French chansons de geste but also Welsh epic poetry, much of it untranslated, all stitched together with vulgar dialect and military jargon more than a century old. Heavy reading, sometimes a slog, but memetic in that way, like a trench filled with mud, though there is lunar beauty on nearly every page, snatches of true music rising above the din.

It’s difficult with the weight of the rifle. Leave it—under the oak. Leave it for the salvage bloke. let it lie bruised for a monument dispense the authenticated fragments to the faithful. It’s the thunder-besom for us it’s the bright bough borne it’s the tensioned yew for a Genoese jammed arbalest and a scarlet square for a mounted mareschal, it’s that country-mob back to back.

Heavy reading, and impersonal, with philology so thick on the page that it occludes the human form. Characters as such are absent from the narrative—even Jones’ stand-in, John Ball, is a cipher—replaced with a slow rolling cacophony of sensory detail—voices and visions, not faces. Dialog is largely unattributed, often reduced to anonymous shouts of command. Gunsmoke and gunmetal, mud and blood, all are rendered with nauseating fidelity, but who these soldiers were, huddled amongst the wreckage, is pointedly reduced to what can be said on a tombstone: a name, a rank, a simple span of life.

Cloud and Chime by Kiyoshi Kurosawa

I was feeling down a few weeks back. After some promising leads for publishers, interest in my translation of Late Summer seemingly vanished. I was left with a depressingly spare inbox (horror of email is a bourgeois affectation). But feast or famine, along with a universally glacial pace, is the cost of admission in the book trade. So to take my mind off all that, I decided to watch some recent films by the prolific Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, two of the three he released last year. I have yet to see Serpent’s Path, a French remake of a film he did in the 90s.

I find Kurosawa’s work oddly comforting. I don’t mean to be deliberately perverse here, even though it is often exceedingly gory and psychologically unsettling. What comforts me is how tightly he controls mood and narrative. The suspense will be suspenseful. The horror will be horrific. The mystery will be mysterious. It’s practically tautological. Even if what happens onscreen will be upsetting, I know I’ll be guided there by a sure hand. We never get what’s advertised to us these days. It’s so refreshing when we do.

Kurosawa is called a “genre filmmaker” and this feels accurate but not complete. Cloud is an action thriller, about a shady online reseller who makes some violent enemies. Chime is psychological horror, about a culinary instructor whose life unravels after a student hears a mysterious chiming noise. So far, so promising, but Kurosawa ends up more delivering on those conceits. The climatic shootout in Cloud thrills in the way a climatic shootout should, with antagonists trading magazine after magazine of ammo in an abandoned factory. But the gunplay limps along comically. The shooters can’t hit very much—accurate for in a place like Japan, with its severe gun restrictions—with one notable exception that should not be spoiled. Chime features the kind of theatrical kills demanded by slasher aficionados, but one in particular, a knifing, comes so unexpectedly and is performed with such an inhuman lack of affect that it crosses the line from “genre” into something that is, a for a brief moment, not entertainment at all.

Film—along with literature—is in such a bad state that conventional pleasures are hard to come by. How much rarer is it then to have a genuine auteur who can bend those conventions at will?