New Pamphlet Out: Some Essays by Heinrich von Kleist

Some thoughts about hand-making (and hand-promoting) a very small book

News and Sundry

The critics Dan Sinykin and Johana Winant have a new book out through Princeton University Press, Close Reading for the 21st Century. Like Dan’s previous book, Big Fiction, this one takes on an ostensibly obscure subject in academic literary studies and demonstrates how it affects our culture as a whole, not just professors and students. From Princeton’s website: “Close reading—making an argument based in close attention to a text—is the foundation of literary studies. This book offers a guide to close reading, treating it as a skill that can be taught and practiced. It first explains what close reading is, what it does, and how it has been used across theoretical schools ranging from affect studies to Black studies to queer theory to Marxism. It then presents a series of master classes in the practice, with original contributions by scholars from a range of different institutions. Finally, it provides practical materials, worksheets, and suggested activities for instructors to use in the classroom. The tone throughout is encouraging and accessible, inviting readers of all backgrounds to hone their craft.”

A week or so ago there was an online dustup about the magazine n+1 and the salary they were offering to a prospective editor. Instead of revisiting the whole silly affair, it’s far better to read n+1 contributor Sam Dembling’s appreciation of the folk singer Michael Hurley, who died earlier this year at the age of 83. As someone who met Hurley a few times, while playing DIY shows in Portland, Oregon, Sam’s profile jives well with what I remember of him—an accomplished slacker, a beautiful bum. “I didn’t enjoy the process of applying for gigs, that determination to penetrate things, all this trouble you had to go through,” Hurley told The Guardian in 2021, “I preferred playing parties. Little gatherings. Drinking with friends, hopping across the river.”

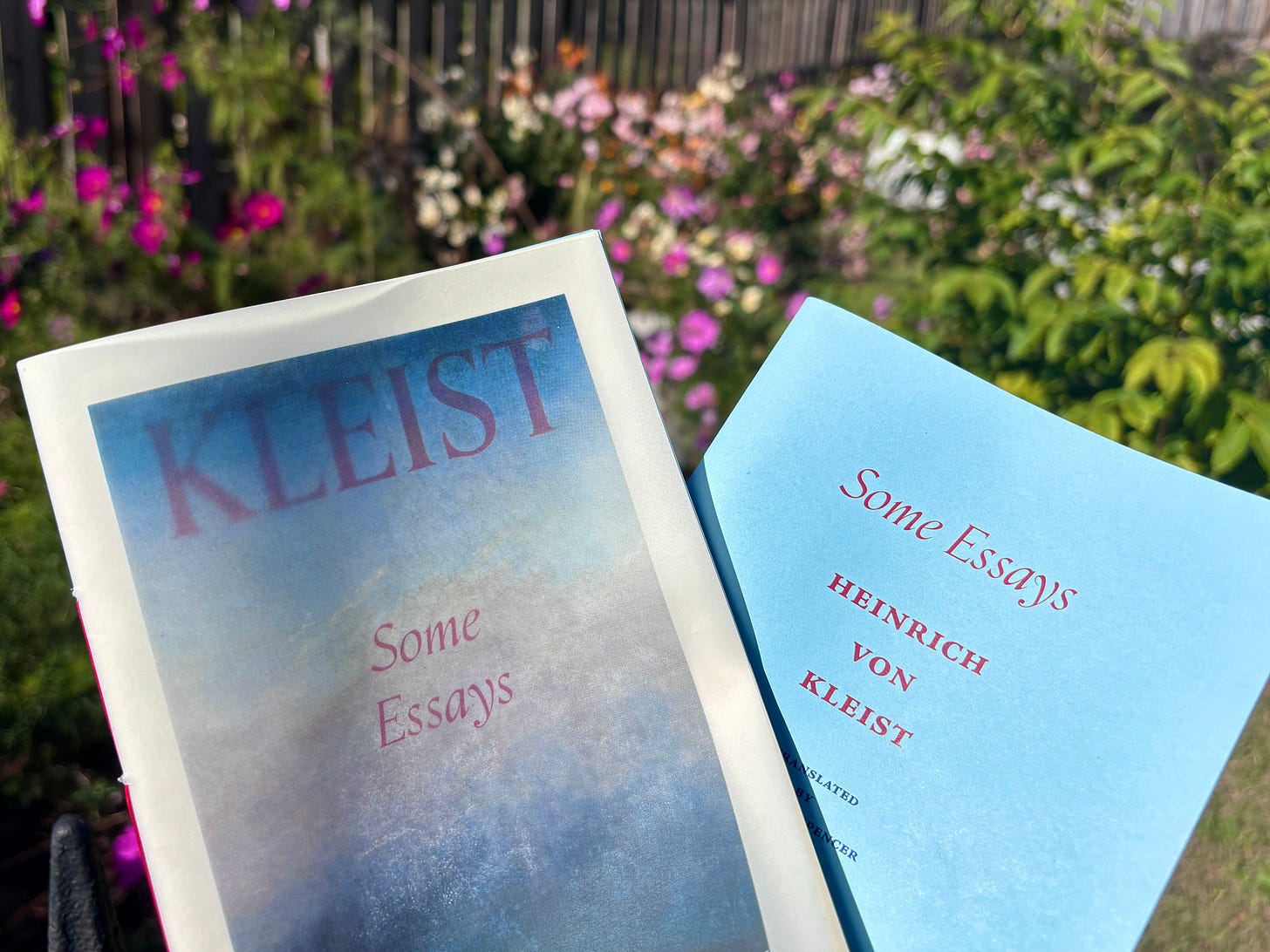

Product Photography

I don’t have the equipment to do proper product photos—a lighting rig, a backdrop cloth, et cetera.—so whenever I have some kind of new book or other piece of printed matter to sell, I’ll go out into the neighborhood and try to use whatever happens to be of visual interest as a backdrop instead. Earlier this week, it happened to be the autumn flowers that were still blooming effusively in the graveyard of the neighborhood Episcopal church. I chose not to shoot inside the graveyard—my preference is to ask neither for permission nor for forgiveness—but rather to shoot along the wrought-iron fencing that separates the graves, some of them more than two centuries old, from the usual narrow residential Philadelphia street that fronts the church. I think the photos look nice, if in an unprofessional sort of way.

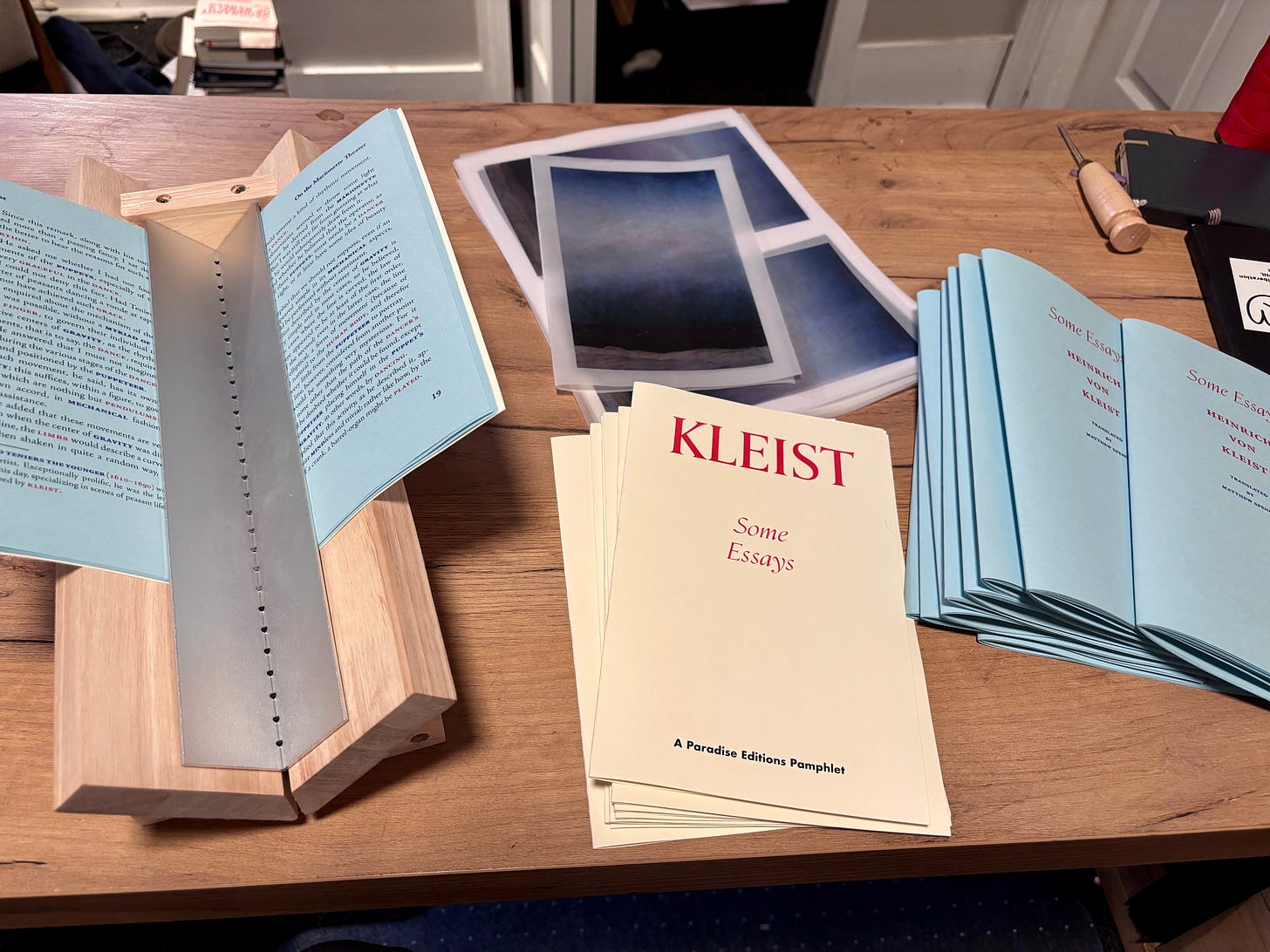

The same could be said of the binding setup on my desk—just a wooden cradle, for punching holes in paper, along with the various printed pages that make up this new pamphlet. When I posted a photo online, a small German publishing house, which focuses on textual criticism, replied that my setup seemed “very practical”. And a cradle is a very practical piece of equipment—well, it’s practical if you happen to be hand-sewing the spines of books and other printed matter. It seems quite exotic, antiquarian, but cradles are easy enough to acquire, sold through specialty craft suppliers as well as through major online retailers. I paid $30 for mine. It’s sturdy, simple. It will outlast my body or at least outlast my ability to sew.

So what kind of pamphlet am I talking about? Have I set up enough context for you to even know what I’m talking about? I don’t know. Anyway, I’m talking about a pamphlet of Kleist translations, some of which were recently featured in this newsletter. You can read them here and here. There are other Kleist essays, “print exclusives” as we call them in the publishing trade, along with an introductory essay by me providing some additional context for the pieces. Below is the “jacket copy”, another professional term, meaning the descriptive text that appears on book that tells you what kind of book the book is.

Can a work of art reject its viewer? What if human beings have no control over their actions? What if recognizing this was the key to absolute freedom? These are the some of the questions posed by Heinrich von Kleist in this collection. Published in rapid succession during the last year of his life, these brief but challenging essays present the finest distillation of Kleist’s philosophical thought.

Heinrich von Kleist was a German-language novelist, dramatist, journalist, purported spy, newspaperman, and poet. Best known in his own time for his theatrical works, he is perhaps most famous today for the short novels, Michael Kohlhaas and The Marquise of O.

This is a lot of trouble to go through for 36 pages of text. Granted, I think I did a good job translating these pieces, and length is not an absolute measurement of difficulty. “On the Marionette Theater” was particularly taxing. There are puns and rare words, the usual lexical knots I preoccupy myself with. It’s not the most difficult translation I’ve ever had to do—that’ll probably always be Jean Paul—but nothing easy or relaxing either. I still don’t quite get why I do this, but, as always, I really hope some readerly pleasure comes your way by indulging these marginal pursuits of mine.

This is really inspiring. It makes me wonder--for authors going the self publishing route, why don't they just go all the way and actually print the books themselves? This would take more work, obviously, but it seems possible.