On the Marionette Theater by Heinrich von Kleist

A translation from the Berliner Abendblätter

Like many of Heinrich von Kleist’s best known writings, this short philosophical dialog appeared semi-anonymously in the pages of the Berliner Abendblätter, the daily newspaper he edited from late 1810 to early 1811. Since Kleist burned his manuscripts prior to committing suicide, and was otherwise reticent in correspondence about his work, “On the Marionette Theater” is difficult to date. However, the year 1801, mentioned at the beginning of the dialog, was pivotal for Kleist. While living in Berlin, he read a book of “Kantian philosophy” an event that was “painfully shocking” to him, so he wrote to his fiancée Wilhelmine von Zenge.

What that particular book was, whether it was from Immanuel Kant himself or from a commentator, has never been established, but it did precipitate a mental crisis, one that would have decisive effect on Kleist’s short life, which, at the age of 24, was already two-thirds over. “An unspeakable emptiness filled my innermost being”, he wrote. Later that year, Kleist travelled to to Paris and then to Thun in Switzerland. He broke off his engagement with Wilhelmine and began his literary career in earnest, writing The Family Schroffenstein, a tragedy about feuding families in medieval Swabia. The play was ignored in Kleist’s lifetime and remains little staged to this day.

If you would like to read more Kleist translations, excerpts from the Berliner Abendblätter can be found at Harper’s Magazine as well as through my newsletter: here, here, and here. A short essay about translating Kleist’s work can be found at the wonderful journal Hopscotch Translation. Anecdotes, a collection of the Kleist translations published in 2021 through Sublunary Editions, has recently fallen out of print (though not through lack of demand) and I’m seeking a new publisher for a revised and expanded edition. I could do it myself, but if any other publishers are interested in picking up the book, let’s get in contact.

Thanks to Michael P. Daley at the great eclectic and esoteric press First to Knock, who first commissioned this translation in 2023. A previous version appeared in FTK’s The Publication, an irregular, print-based zine of “new writings, exhumed un-classics, translations, art, and anything else deemed relevant by the editorial brain trust.” Subscribe to them!

During the winter of 1801, which I spent in the city of M—, I chanced to meet one evening, at a public garden, Herr C—, who had recently been employed as first dancer for the opera, and who had found extraordinary success with the public there.

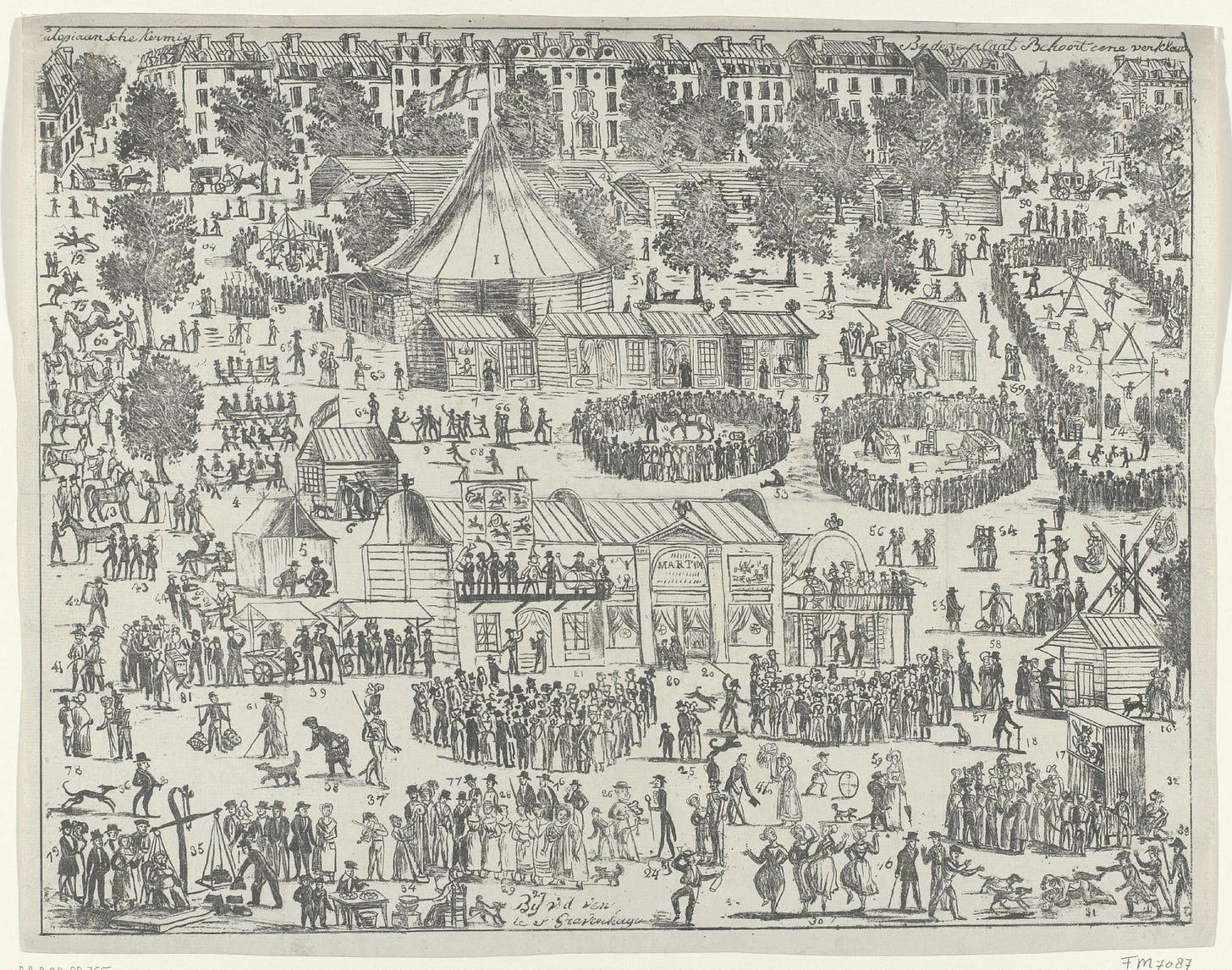

I said that I had been astonished to see him, on several occasions, at a marionette theater, which had been cobbled together on the market square and had provided, with its little dramatic burlesques, interwoven with song and dance, amusement for the rabble.

He derived, he assured me, much pleasure from the pantomime of these puppets, and made it clear that a dancer, if he wished to cultivate himself, had something to learn from them.

Since this remark, along with his tone of voice, implied more than a passing fancy, I sat down beside him, the better to hear the reasons for such a strange assertion.

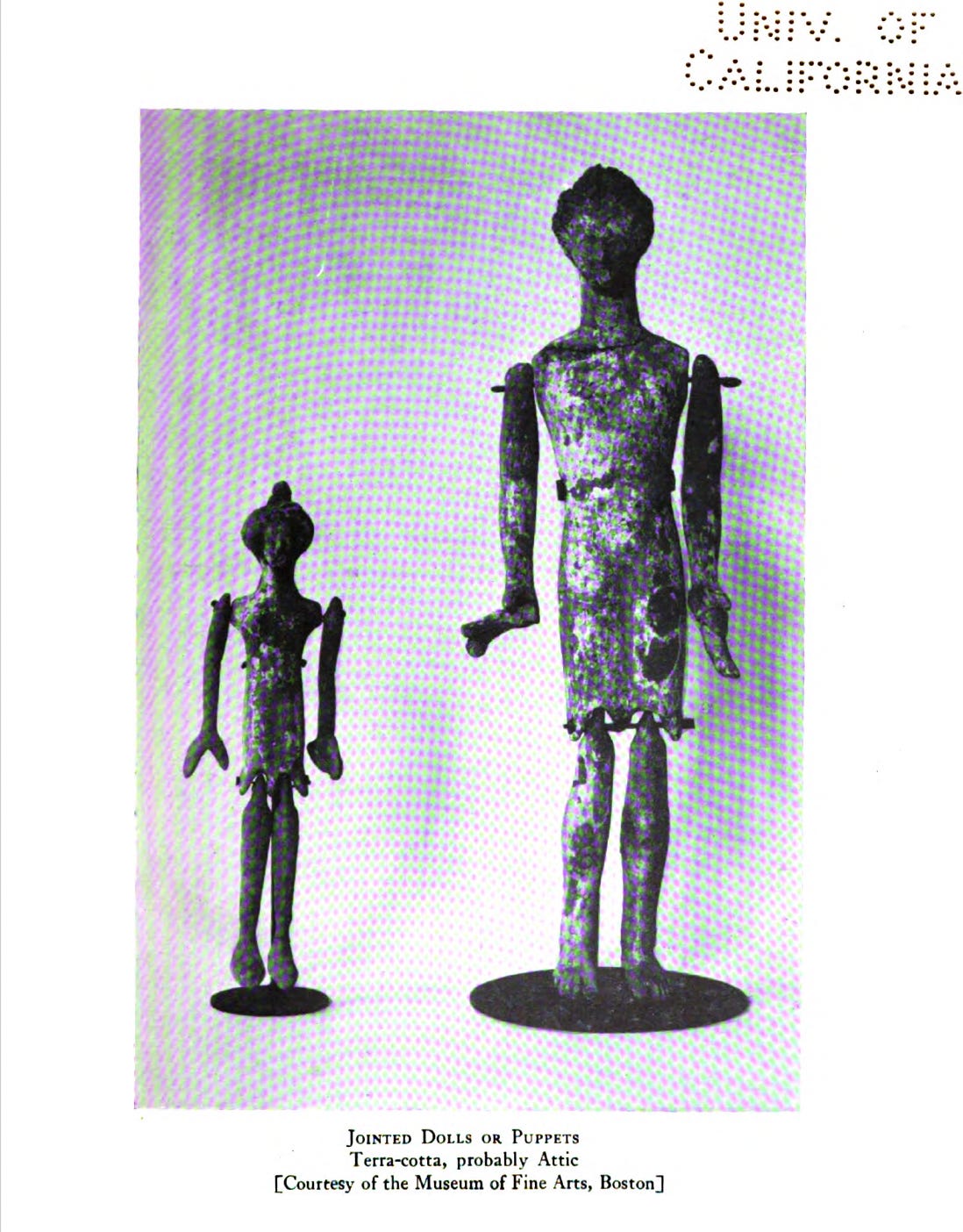

He asked me whether I had not found certain movements of the puppets, especially of the smaller ones, very graceful in the dance.

I could not deny this fact. Had Teniers painted a quartet of peasants dancing a ronde at rapid pace, he could not have achieved such grace.

I enquired about the mechanism of these figures, how it was possible, without a myriad of threads on the finger, to govern their individual limbs and respective centers of gravity, as the rhythm of their movements, that is to say, the dance, required.

He answered that I must not imagine that each limb, during the various stages of the dance, had to be pulled and positioned by the puppeteer.

Each movement, he said, has its own center of gravity; this suffices, within a figure, to govern it; the limbs, which are nothing but pendulums, follow of their own accord, in mechanical fashion, without further assistance.

He added that these movements are very simple; that even when the center of gravity was directed in a straight line, the limbs would describe a curve; and that often, when shaken in quite a random way, the whole puppet would assume a kind of rhythmic movement, resembling a dance.

This observation seemed to throw some light on the pleasure he derived from the marionette theater. But I was still very far from guessing at what conclusions he would subsequently draw from it.

I asked whether he believed that the operator, as the ruler of these puppets, must needs be a dancer in his own right, or at least have some idea of beauty in dance.

He replied that we should not suppose, even if an activity appeared simple in its mechanical aspects, that it could be performed without sentiment.

The line described by the center of gravity is indeed very simple and in most cases, so he believed, straight; in cases where the line is curved, the law of its curvature appeared to be at least of the first order, at most of the second; even in the latter case, the line is merely elliptical, a form of movement (because of the joints) natural to the human body, and therefor requiring very little from the operator to portray.

This line, however, considered from another point of view, would be something very mysterious. For it would be none other than the path of the dancer’s soul; and he doubted whether it could be found, except by the operator placing himself in the puppet’s center of gravity, in other words, by dancing.

I replied that this activity, as he described it, appeared quite mindless and trivial: rather like how, by the turning of a crank, a barrel-organ might be played.

By no means trivial, he replied. On the contrary, the movements of the fingers relate quite intricately to the movements of the puppets attached to them, rather like the relation of numbers to their logarithms, or asymptotes to their hyperbola.

Meanwhile, he believed, the last fraction of human volition could be removed from the marionettes, and their dance wholly transposed into the realm of mechanical forces, brought about, just as I had imagined it, by the turning of a crank.

I said I was astonished see him dignify this parody of theater, contrived for the masses, with his attention. Not only did he believe it capable of higher artistic development: he seemed directed toward that very end himself.

He smiled and ventured to say that, if a craftsman were to construct for him a marionette according to the designs that he supplied, he would, by means of the same, perform such a dance than neither he nor any skilled dancer, Vestris himself not excepted, could ever replicate.

Have you seen? he said, as I silently cast my eyes to the ground: have you seen the mechanical protheses which English artisans make for unfortunates who’ve lost their limbs.

I said no; I had never seen the like.

A pity, he replied, for if I tell you that those unfortunates can dance with them, I’m almost afraid you won’t believe me. — Dance? What am I saying? The range of movement is indeed limited; but those who have such legs to stand on dance with an ease, grace, and fluency that astonishes any thinking mind.

I remarked, in jest, that he had found his man. For the same artisan, able to build such remarkable shanks, could doubtless assemble a whole marionette according to his specifications.

How? I asked, while he, for his part, stared at the ground, a little abashed: how are these specifications, which you demand of the artisan, to be fulfilled?

With nothing, he replied, that wasn’t already found there; balance, mobility, and ease—but each to a higher degree; and especially in a more natural arrangement of the centers of gravity.

And the advantage of such a puppet over living dancers?

The advantage? First, my excellent friend, a negative advantage: namely, that they affect nothing. — For affectation, as you know, appears when the soul (vis motrix) divests itself of gravity of the moment. Now, because the puppeteer, by thread or by wire, has nothing in his power other than what gravitation provides, all remaining limbs are, as they should be, pure dead pendulums, which follow the basic law of gravitas; a marvelous quality, which we look for in vain in the greater part of our dancers.

Watch Madame P—, he continued, when she, playing as Daphne, is pursued by Apollo and glances back to him: her soul sits somewhere at the base of her spine, she bends as if it would snap in half, like a naiad from the school of Bernini. Watch young Monsieur F—, when, as Paris, he stands with the three goddesses and hands the apple to Venus: his soul (it is fearful to behold) actually settles in his elbow.

Such blunders, he added finally, are inevitable, since we have eaten of the Tree of Knowledge. But Paradise is locked and barred, and the Cherub is behind us; we must take a journey around the world, to see if a back door has perhaps been left open.

I laughed. — True enough, I thought, the mind cannot err where none is present. But sensing that he had more to say, I asked him to continue.

Furthermore, he said, these dolls have the advantage of antigravity. They know nothing of the inertia of matter, which of all properties is most obstructive to the dance: the force that lifts them into the air is greater than the one that shackles them to the earth. What would our dear Madame G— give to be sixty pounds lighter, or to have a counterweight of that size to aid her in her pirouettes and entrechats? The puppets, like elves, need only touch the ground to revive, by that momentary inhibition, the spring in their step; we need it to rest and recover from the exertion of the dance: a moment which is clearly not of the dance itself and about which nothing can be done, other than to make it pass as swiftly as possible.

I said that no matter how skillfully he might pose his paradoxes, he could never make me believe me that a mechanical man could embody grace better than any human body.

He replied that it was absolutely impossible for anyone to be as limber in the limbs as a mechanical man. Only a deity, in this domain, could compete with mere matter; and it is here where the two ends of the round earth meet.

I grew more and more astonished and did not know how to answer such bizarre assertions.

It would seem, he said, taking a pinch of snuff, that you have not read the third chapter of Genesis with attention; and whosoever remains ignorant of the first stage of human development cannot speak of following stages, much less of the final one.

I said I knew all too well of the disorders that consciousness can produce in the natural grace of mankind. Through a simple remark, a young acquaintance of mine, before my very eyes, so to speak, lost his innocence, and despite every conceivable effort, his paradise was never regained. — But what conclusions, I added, could be drawn from this?

He asked to hear more about the incident.

About three years ago, so I told him, I was bathing with a young man whose form and deportment radiated a most wonderful charm. He must have been sixteen or so, and only the first traces of vanity, induced by the favor of women, could be seen in offing. As it happened, we had just viewed, in Paris, the statue of a youth pulling a thorn from his foot; casts of it are well known and can be found in most German collections. A glance into a large mirror, just as the youth was placing his foot on a stool to dry, reminded him of this; he smiled and told me about the discovery he had made. At that very moment, in fact, I had noticed that same resemblance; but to test the grace within him, and to provide some salutary response to his vanity: I laughed and replied—you must be seeing ghosts! He blushed and raised his foot a second time to show me; but the attempt, as could have easily been foreseen, failed. Confused, he raised his foot a third and then a fourth time, probably he raised it ten more times: in vain! He was unable to produce the same movement again — indeed, the movements he did make had such a comical effect that I had trouble holding back my laughter: —

From that day on, as if from that very moment, the young man underwent an incomprehensible change. He would stand for whole days in front of the mirror; one charm after another left him forever. An invisible and incomprehensible force, like a net of iron, seemed to enclose the free play of his gestures, and when a year had elapsed there was no longer any trace of the sweetness which those surrounding him had once feasted; there yet lives a man, a witness to that strange and unfortunate event, who can confirm word for word as I have related it. —

I must take this opportunity, said Herr C—, to tell you another story, the relevance of which you will easily discern.

On a trip to Russia, I found myself on an estate belonging to a Herr von G—, a Livonian nobleman, whose sons practiced fencing rigorously at the time. The older one, who had just returned from university, acted the virtuoso, and, when I was in his room one morning, offered me a rapier. We fought; but it so happened that I was the superior; passion confused him; almost every thrust I wielded made a hit, and, at last, his rapier flew into the corner. Half in jest, half in pique, he said, retrieving his rapier, that he had found his master: but everyone in the world will eventually find his, and henceforth he would lead me to mine. The brothers laughed out loud and cried: Away! Away! Down to the woodshed! And with that, they took me by the hand and led me to a bear, which Herr von G—, their father, had raised on the estate.

I was astonished to find the bear standing on his hind legs, his back leaning against a post to which he was tied, his right paw raised and ready to strike, looking me direct in the eye: that was his fencing posture. Facing such an opponent, I thought I was dreaming; but Herr von. G— called out, Strike! Strike!... and see if you can teach him anything! Having recovered a little from my astonishment, I lunged with my rapier; the bear made a brief swipe with his paw and parried the thrust. I tried to ensnare him by feints; the bear did not move. I lunged at him again, with instant dexterity, and, had he been a man, I would have stuck his chest without fail: the bear made another brief swipe with his paw and parried the blow. Now I was in almost the same predicament as the elder brother had been. — The solemnity of the bear further robbed me of my composure, thrusts and feints alternated, and I was dripping with sweat: in vain! For not only did the bear, like the firstborn fencer of the world, parry all my thrusts; he didn’t even bother (no fencer of this world could match him) making feints of his own; he stood eye to eye with me, as if he could read my very soul in these maneuvers, his paw raised for the strike, and did not stir from his place, as though my thrusts were not meant in earnest.

Do you believe my story? he asked me.

Utterly, I cried, with delighted applause. It is so plausible, I would believe it coming from any stranger, all the more so coming from you.

Now then, my excellent friend, you are in possession of all you require to understand my point. We see how, in the organic world, as reflective thought grows dimmer and dimmer, grace emerges ever more radiant and supreme. — But just as two intersecting lines, converging on either side of a point, intersect once more, after having passed through infinity, and just as our image, as we approach a concave mirror, vanishes into infinity, only to reappear before our very eyes, so will grace, having likewise traversed the infinite, return to us, and so appear in a bodily form that has either no consciousness at all or an infinite amount of it, which is to say, either a puppet or a god.

That means, I said, somewhat distracted, we would have to eat of the Tree of Knowledge a second time, in order fall back into a state of innocence.

Indeed, he replied, and this would be the final chapter in the history of the world.