Ulysses in the Alps, Ulysses in Seattle

On bickering about a book on the site of a mass shooting

For a short time in the mid-2010s, I would occasionally attend a monthly meetup of science-fiction writers in Seattle. What exactly these events were is sort of difficult to define a decade or so later: part reading series, part open mic, part writing critique session. In any case, they were held at a favorite café and small concert venue, Café Racer, and for the most part I was just glad to hang out at my old neighborhood spot, having moved away from the University District a few years before. I wasn’t writing science-fiction, or at least I wasn’t writing it along strict genre lines, but I did have an appreciation for the classics, as well as a literary-historical interest in its origins, roughly from late 17th to the early 19th century. Think not only of Mary Shelley but also, remarkably, of Cyrano de Bergerac and Casanova.

These interests were unpopular with the other writers who attended the meetup. Not only were they uncomfortable with the genre’s historical association with eugenics, male chauvinism, and colonial expansionism, but they also held a concomitant (and oftentimes stronger) aversion toward so-called literary fiction or even literary ambition in general. To them, both tendencies—the chauvinistic and the literary—were artifacts of a past best overcome if not forgotten entirely. I never, not as far as I can recall, pressed my own marginal pursuits and preferences on the rest of the group, at least not during their formal meetings, except for one particular night.

I had been seated at a small table in a back room of the café. There were about five or six others seated randomly with me, gathered to critique each other’s work. A woman (I feel safe in this recollection, as pronouns had been introduced) began to talk off-topic, (I’m not sure why) about James Joyce and how he was a writer who “sucked so much” and who “just wrote ungrammatical nonsense” that “nobody really read anyway”. It was the usual anti-modernist boilerplate, but I happened to have —as if I had been furnished with some preprepared argument for a debate tournament—a copy of Ulysses in my tote bag, specifically the excellent Oxford Classics annotated edition, which I pulled out and set on the table.

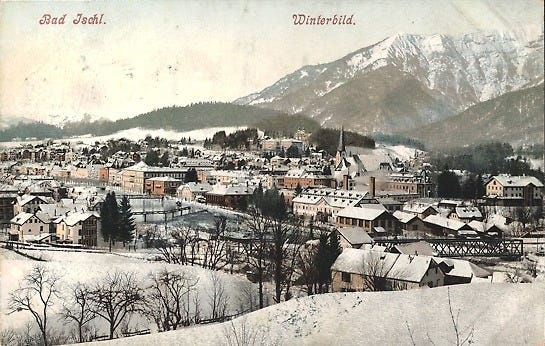

Despite having read and loved Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (typically enough) in high school, I had only gotten through Ulysses relatively recently, during a post-college stint teaching English in rural Austria. For reasons I can no longer clearly remember, I took that Oxford Classics edition with me, schlepping it on the transcontinental flight to Europe and the subsequent train journey from Salzburg to Bad Ischl, the historic spa town where I was posted; maybe I’d brought in anticipation of boredom and loneliness. That seems likely.

The winter I spent in Bad Ischl was particularly snowy, even by the standards of the Salzkammergut, an astoundingly beautiful district of clear Alpine lakes that had been settled since the late Neolithic and for that reason designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, though the scenic component was not always apparent, especially in winter, when the landscape was obscured by capricious mountain weather. But the place always had atmosphere in abundance. The front window of my garret apartment—yes, it was a garret apartment—looked out on the Totes Gebirge, the “Dead Mountains”, and icy gusts would blow down from the high limestone plateau, shaking the Christmas lights strung along the narrow village roads and piling the snow into heavy drifts along the sidewalks.

That Christmas season, my teaching schedule, already lean in anticipation of the winter break, was canceled entirely, and so I decided to commit to Ulysses. It seemed an appropriately perverse occasion to read a novel famously set on a single day in June. There wasn’t much else to do besides watching German-dubbed episodes of Two and a Half Men and getting drunk on mulled wine at the Christmas market. Seemingly no degree of harsh winter weather could cancel the Christmas market. But as it turned out, I didn’t need so much time, and I tore through the book in about a week, only consulting the voluminous endnotes and scholarly essays when it was absolutely necessary. Needless to say, I didn’t understand everything, or even half of the things, that I read, but I did enjoy it. The local dialect could be just as impenetrable.

If my stay in Austria convinced me of anything it was that I was not meant to be a teacher. If it convinced me of anything else it was that I could be marginally happy anywhere I could take long walks in the forest and also—almost a century’s worth of received opinions notwithstanding—that I enjoyed Ulysses. Back in Seattle, I began to revisit my favorite parts, especially the hallucinatory “Circe” chapter, in which Bloom and Daedalus meet at a brothel in Dublin’s red-light district. The jumble of characters (some of them from other books) was no less disorienting, but I was also still viscerally shocked and amused by the chapter’s psychosexual fantasmagoria, especially the hero Leopold Bloom living out repressed impregnation fantasies. The guy would have loved browsing tumblr.

I wasn’t going to tell this woman at Café Racer the particulars of “Circe” or any other chapter. Joyce’s own frequenting of prostitutes certainly would not have endeared him to her either. Instead, I simply said that I liked Joyce’s writing and that I happened to be rereading him, producing my own copy, complete with its cracked spine and greasy, dog-eared pages, as proof. Her response was that I was just “a graduate student” and so I had to “pretend to like Joyce” in order to fit in with my colleagues. I explained that I hadn’t studied English literature or Irish literature but German literature, and only at the undergraduate level, and that it was common, very common in my experience, for academics to be just as suspicious of canonical literature as she was, if in a more systematic way, or else become jaded about the subject from years of studying it professionally with diminishing career prospects. I wasn’t “defending him, defending that overrated writer” as she said, but defending myself and my own tastes: “No, I don’t go to college anymore…no, I really do like him…I really do…honest.”

That must have been eloquent enough because, after spluttering for a moment, the woman left our table. I was worried that she might complain, having, by her simple absence, lost the argument, but none of the organizers approached me. I stopped going to the meetups soon after that. I didn’t feel burned by the experience—far from it—and I hope the woman didn’t either. The science-fiction events were well organized, and I admired a lot of the writing that was presented at them. There was a much higher standard, I felt, than at the other writer’s groups in the city, even those sponsored by The Richard Hugo House, a large and well-respected literary nonprofit. I just realized that I had my own fundamentally different goals as a reader and a writer. I cared not only about the craft but the history of that craft. And with even less speed and shrewdness, I also realized that the culture that supported that sort of argument, what made it possible to be in the same room together arguing about James Joyce, was about to be erased, was actually in the process of being erased, and what was replacing it was unimaginably more crude and stupid than anything offered during the open mic. In a very palpable sense that erasure had already been achieved.

So far I have avoided mentioning an event that in retrospect must have been a factor in me wanting to leave Seattle. This is not because of any deliberate rhetorical strategy but simply because the event, however horrible, has slowly been fading from memory. On the morning of May 30th 2012, a frequent but disgruntled customer of Café Racer returned and, after he was told to leave a final time, fatally shot four people there, two customers and two employees, a fourth person, another employee, surviving with serious injuries. Those killed included Drew and Joe, members of a local folk-punk band, God’s Favorite Beefcake, whom I vaguely knew from going to shows at Café Racer and elsewhere. The gunman then fled the scene, later killing a random woman elsewhere in the city and stealing her car, before he ultimately turned the gun, or rather one of his guns, on himself.

Even when I lived close to Café Racer, during my time at the University of Washington, I never went there except in the evenings, but for a year or more, basically until I left for Austria, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I could have been there. A dear friend of mine, Abi, certainly could have. She lived a few houses over and regularly visited the café at the time when the shooting happened. I would read a description of the killer, I would see his face on reproduced security footage, and I couldn’t help but remember me and my friends there with him, even though such a memory would almost certainly be false. I couldn’t help but think that way, picturing us together, me and my friends just sitting there, eating bad food, drinking bad coffee, talking about music or books or whatever while the shooter, off to himself, planned on killing us and every other person in the room. It may very well have happened like that, but having a definite memory of it seems impossible. The time of day is wrong, for one thing.

In the days and weeks after the shooting, I would see random Facebook commenters insisting that the victims were at fault for not being armed at the time, as if anyone reasonable would have felt the need to carry a handgun, or multiple handguns, into Café Racer on a Wednesday morning. In Austria, my students and co-teachers were shocked, though in their stereotypical understanding of America not surprised, to hear that I knew or rather was vaguely acquainted with the victims of a mass shooting and that I had had a chance, an outside but not insignificant chance, of becoming the victim of a particular mass shooting myself. It confirmed every other prior assumption they had about my country. It was like telling them I ate hamburgers every day, another stereotypical belief that these kids harbored, maybe the teachers too, and which was impossible to disabuse them of following that other, more weighty admission.

Café Racer had, understandably, an irregular history following the shooting. I can’t recall exactly how many times it reopened and then closed again—“at least twice”, so the Wikipedia entry states. I would like to say that it was “never the same” but that vague cliché has too strong of an emotional valence for what I felt on coming back to the US.. The initial fear and outrage at the shooting was replaced by the dull grind of living in a city that was fast becoming overwhelmingly unaffordable for writers, musicians, and service workers, the kinds of people who were murdered that day. Seattle had become world-famous not from its tech industry but for its cultural scene, and the city had repaid that debt by shuttering its cultural venues, one way or another.

I was happy to go back to Café Racer whenever I could, but other places, and the other interests that those places fostered, gradually took over. Nowadays, its memory is most often reduced to that one argument I had there, an argument that I had won, arguably, by stuttering and gesturing toward a book I had randomly brought along with me. Much less often, if I’m being honest, I do also remember Joe and Drew and I try to think about the other people that died that day, not even vague acquaintances but people who had, nevertheless, lived lives very similar to mine, playing in local bands, writing a first novel or first poetry collection, exhibiting a painting or collage on café walls. We all lived such similar lives until they, the unlucky ones, went to Café Racer on a Wednesday morning and were killed for it, some of them executed with shots to the back of the head. It disgusts me to see how typical this story has become.

During the past decade or so, places like Café Racer have become increasingly rare. Coffee costs more. Food costs more. Booze costs more. Rent costs more. Books are one of the few things that don’t cost more, but fewer people are reading them. Amateur art has migrated online, only to be replaced by AI-generated content, devoid of individual personality and social context. The world has been remade in the image of the mass shooter: full of lonely, resentful creeps with murderous intent. It has been remade according to their wishes: those who would participate in any kind of modest cultural life have been driven away, sometimes killed, and the places they once frequented are now closed forever. Whatever faults those science fiction writers had, their vulgarity pales in comparison to our current leaders—university administrators, nonprofit directors, editors-in-chief, producers, publishers, landlords, and so on—who do not even need the pretext of a spree killing to demolish one institution after another.

These are dreary, dispiriting times, but I still hold onto that vision of that shared cultural life. I still cherish being able to read an excellent book, still cherish being able to discuss those books with different people with different views, different values, different backgrounds, in a physical space together. Even when the talk is sharp there is a gentleness to it, a sort of reciprocal grace, that transcends difference. This can’t be reproduced online, not anymore. The slop has crowded it out. But there are still rooms in this world, in Seattle and elsewhere, with good or at least tolerable company, full of people who deserve to be heard, or at least heard out. There is fellowship to be had. Merry Christmas.

Thanks for this. As someone who was also a wannabe writer in Seattle at the same time—attended SPU from 08-11, and remember the Cafe Racer shooting pretty well, although I never went there until one of its reopened iterations—it’s interesting to revisit that almost religious aversion in that town at that time to the idea of actually valuing a writer like Joyce. So many arguments with my friends in my apartment in Lower Queen Anne.

Reading this was like looking at a snapshot from my own college days in some ways—I was on a trip when the SPU shooting happened the next year, but it happened in a building I took tons of classes in, and the surreality of the experience was hard to shake. Anyhow: thanks for writing, and posting this. Merry Christmas, sir.