Should Translators Use AI?

A limited defense

I use “AI” for all my translations. This isn’t deliberate—quite the opposite—but rather that Google and other tech companies force their use on me. (I put scare quotes around the term “AI” because I don’t believe the technology possesses any real intelligence to speak of.) And yet, large language models, the more specific, less editorializing term for the technology in question, are built into practically every commonly available software program and search engine; the only way to opt out is to run specialized plugins and browser extensions, an unfeasible option for me, since my ancient and decrepit MacBook can only handle so much as it is. I can’t think of a better example of how a so-called technological progress makes work more difficult and tedious. I suspect it’s that way with almost everyone. It came as no surprise when a recent study was released, showing that the use of “AI” even slows down the work of software developers, programming being the one application that it supposedly excels in. Rather than supercharging productivity, “AI” increases the amount of toil in the world.

I don’t know how it relates to software development, but for me, “AI” technology has been deleterious because it artificially adds steps in the translation process. If I want a useful result for a query, it’s much better to start with the internal search at JSTOR, HathiTrust, Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache, or any other online resource, rather than trust Google to direct me there on its own. Sometimes it’s even quicker to consult a printed reference work. All this eliminates the need for Google in the first place, a pointless sacrifice of the website’s basic functionality, since I can’t recall ever having Google’s LLM provide me with a useful solution to a research question.

So I was surprised and a little put off when I heard that Allie Whittemore used ChatGPT for her translation of Attila by Aliocha Coll, as she relates in her introduction to the novel. I haven’t read Attila yet and don’t understand Spanish at a high enough level to confirm the accuracy of the translation, but I’ll take it on trust that the quality is there. The publisher, Open Letter, is highly respected, and Whittemore has enough publications and academic credentials to demonstrate her competency. So why even use ChatGPT?

Now, having read through Whittemore’s introduction (publisher Chad W. Post has helpfully published on the Open Letter’s Substack), I’m beginning to understand why she might have needed the extra help. Attila is a postmodern experimental novel, and it brims, so Whittemore relates, with neologisms and portmanteaux, a large portion of which, being inventions of the author, don’t appear in any commonly available dictionary or reference work. They probably don’t appear at all.

It’s a problem I encounter all the time in my translations from German. Whether it’s writing from historical writers like Jean Paul, or from contemporary writers like Wolfgang Hilbig, much of what I translate is deliberately obscure, enough so that native speakers of German might have a difficult time parsing what is meant by a particular passage. Even where there is a large scholarly apparatus for an author, such as Heinrich von Kleist, the experts will disagree, oftentimes vehemently, or else the obscure point doesn’t happen to be of academic interest. Wading into every learned debate might be desirable for an academic translator, especially those who concentrate on a single author or even a single work, but neither I nor Whittemore, it seems, follows that particular career path. So we have to look things up and, when the information is not available, make the best guess available to us, even if it’s no more than hunch.

While thinking about Attila and LLMs, it also occurred to me that I’ve only really used Google, and not of my own volition. I already know how bad it is. But what about ChatGPT? To test it out, I used selections from a recent but already completed translation I did of Das Christbaubrettel, or A Christmas Tree Cabaret, a short play by the Bavarian actor Karl Valentin. Valentin was a major figure in the theater and early film industry in Germany, an inspiration to Bertolt Brecht and Samuel Beckett, but his stage work has largely gone untranslated, presumably because of the linguistic difficulties he presents. This is not because Valentin wrote in a difficult and obscure style, quite the opposite; he was a genuinely popular artist, one who is still beloved in his native Munich. The difficulty comes from the Bavarian dialect Valentin uses.

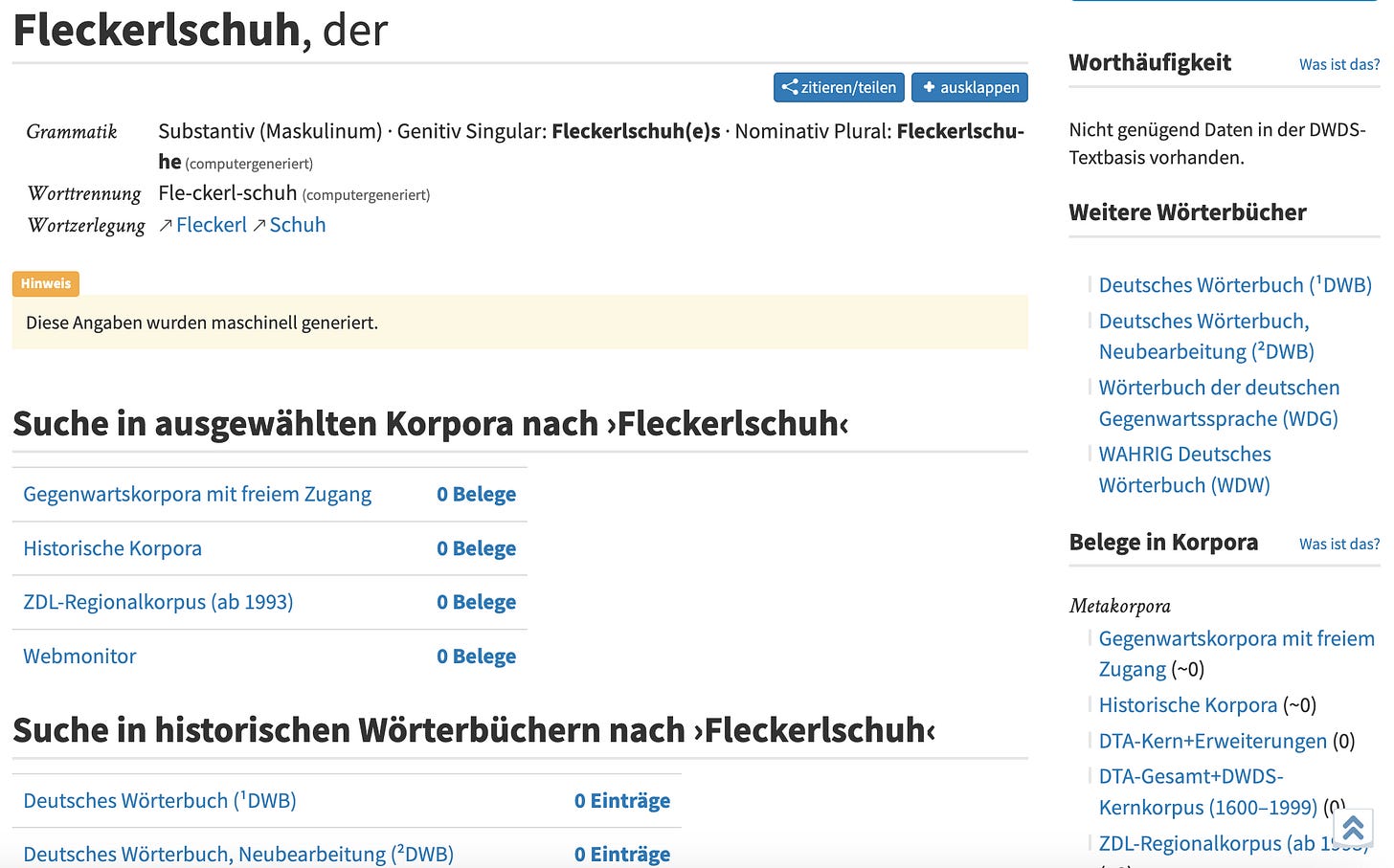

Take, for instance, this piece of stage direction from A Christmas Tree Cabaret: “Die Mutter sitzt in einem ärmlichen Hauskleid mit einer blauen Schürze in Fleckerlschuhen…” The first part is perfectly understandable: “The Mother sits, wearing a shabby housedress with a blue blouse…” But I had to pause at that last word in the selection, “Fleckerlschuh”—it was a word I had never come across before, this despite having spent extensive time in the areas of Austria and Bavaria where the Bavarian dialect is spoken. (“Bavarian-speaking areas of Bavaria” seems like a pleonasm, a redundant statement, but there are other dialects there that are sometimes not mutually intelligible with Bavarian or standard German.) Dictionaries were of limited use, even those that specialized in the dialect. That such reference works exist at all is fortunate, especially dialect dictionaries that are publicly available and digitized, because, even in languages as common as Spanish, they can’t be taken as a given. The German mania for systemization has its definite upsides.

As per usual, the Google “AI” result was useless, worse than useless actually. The LLM associated with “Fleckerlschuh” with dancing, since “Fleckerl” can mean a particular step found in the Viennese waltz. This didn’t seem right, since the scene being described by Valentin is domestic, taking place in a cramped apartment, and the character of The Mother is elderly and poor. But I couldn’t dismiss the possibility out of hand, since Valentin was fond of using absurd humor. A Christmas Tree Cabaret doesn’t even take place on Christmas. Google being useless was all too expected, but the standard reference works were giving me nothing. What was I going to do?

I eventually pieced together, in a manner of speaking, that “Fleckerlschuh” means a patched-up shoe, since the first word of the compound, “Fleckerl”, can refer to a scrap or piece of fabric. “Schuh” is more self-explanatory. That definition seemed right, at least compared with the one Google originally gave me, but I still needed to make sure. The non-LLM-generated search results were few and not particularly helpful, except for a brief article about early 20th-century mountaineering, which describes, in passing, how climbers in the Tyrolean Alps would often use old, worn-out boots. I decided to take a chance and say that “patchwork shoes” was what Karl Valentin meant. That a single word could prove so difficult underscored why he’s so undertranslated, and it became another small mark of professional pride that I could reason through poor-quality or outright misleading information. Could ChatGPT achieve such a result? It turned out that it could.

When I ran the phrase, “What does Fleckerlschuh mean in German?” into ChatGPT, I initially received similarly useless results, the difference being that ChatGPT told me that the word in question did not appear in any standard form of German—nothing I didn’t know already, but nothing outright misleading either. However, when I asked it a slightly different question, “What does Fleckerlschuhen mean in Bavarian dialect?” I got a much more specific and usable answer, the one that I had pieced together myself. This was impressive. I still would have needed further research to confirm it, but the result showed that Whittemore wasn’t completely off base in using ChatGPT. My initial skepticism turned into grudging respect for the technology and for the translator being candid in her account of the process. Wittemore had provided some genuinely useful information.

Would I recommend translators use ChatGPT in their research? I would, if only because it produces more accurate results than Google. I’m not trying to be tendentious or to boost universal adoption of a technology that is actively degrading our climate and straining our power grid, but rather I’m trying to bring some nuance to a subject that is emotionally and ideologically charged. When I made this point on social media, someone responded that translators should use their own expertise and cultural competency to find the definitions of words, but this is an absurd demand to make for someone translating difficult literature like Attila, which baffles native Spanish speakers. Even someone as straightforward as Karl Valentin defeated standard internet searches.

I’m not doctrinaire about the methods that translators use, especially if they’re transparent about using them. If LLM technology eases the difficulty of producing a translation, I don’t see why it shouldn’t be used. My first principle is for the translation to exist. My second is that it should be well-written. The third is that it should not include deliberate and easily avoided errors. So long as the translator doesn’t violate these three principles, I’m not concerned about methods. Whittemore also said that she had a psychic medium contact Aliocha Coll, that seems less of a flash point for controversy than her use of ChatGPT. Why is that? As much as it is good to see readers invested in the future of the artform, I’d rather not have them make judgments about what tools translators should use, at least until they’ve translated a book of their own. With Google and other search tools being as bad as they are now, we don’t have as many options as we used to.

This seems to me a sensible and level headed response. Another thing I was thinking about during this controversy was the material question, as in, money. Everyone knows publishing houses doing translated literature make very little money, if any, and with the cancelling of the NEA grants, they have even less. Reading Whittemore's introduction confirms that the publication of Attila was a labor of love that pretty much revolved around two people, her and the editor. I saw people calling for reviews of the translation from experts, or research assistants helping with the translation, etc. but all this requires money and is simply unrealistic in the current climate. In an ideal world, sure, but we should also recognize that without Whittemore, this book doesn't exist in English.