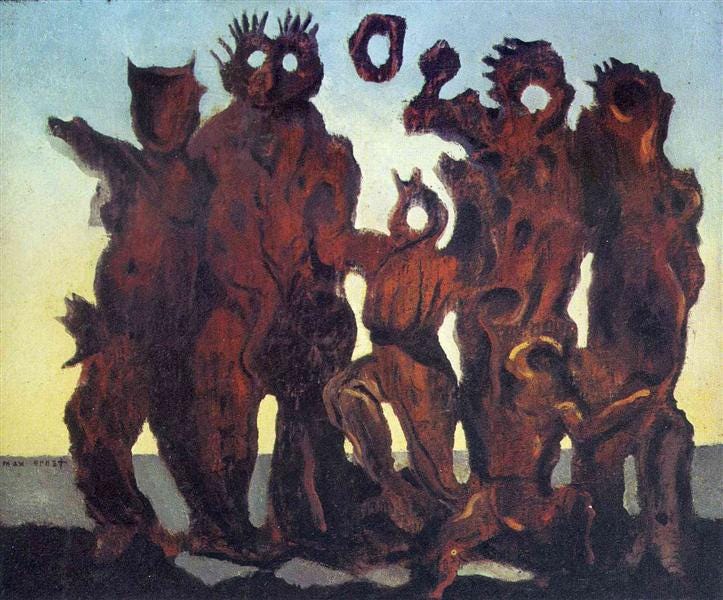

Paradise Bulletin (Oct 29th)

Horror Literature and Literary Horror

I’ve been on some Halloween themed reading, shuttling between classic horror and horror-adjacent translated literature, finding some interesting parallels between. In a recent podcast interview, Brian Evenson, who ought to know, talked about how he saw horror, at least in its written form, as a fictional mode rather than a genre, dependent more on mood and philosophical orientation than recognizable plot tropes. I agree with him wholeheartedly.

The first book I read this week—one that established many tropes—was H.P. Lovecraft’s novella “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” via a dramatized audiobook performance by Ian Gordon. The story and author were formative to me as a reader, and I still enjoy Lovecraft’s writing immensely, with all the necessary qualifications about his racist and eugenic ideology. Much of this is sentimental attachment to childhood media, of course, but I do think Lovecraft is a more interesting writer than is generally credited, even by the pop culture fandom that has grown up around the Cthulhu mythos.

What stood out for me this time was his sense of geographic precision. Lovecraft describes the built and natural environment around the fictional Innsmouth quite vividly, and not always with the same characteristic boilerplate. The streets are named, their condition and directions specified, forming a believable city plan. This strikes me as more than just adventure story verisimilitude. Lovecraft describes actual places in his native Providence in much the same way. He evokes real atmosphere and so comes by his cluttered syntax and archaic verbiage honestly. They are tools for enhancing a singular vision. The immortal humanoid fish frogs of the story are ridiculous. But they are striking and memorable, their town as well.

The other book I read this week is far less famous but more believably horrific: Old Rendering Plant by Wolfgang Hilbig, translated by Isabel Fargo Cole. Cole is also the translator of the recent, complete edition of Adalbert Stifter’s novella collection, Motley Stones. I can see why she selected those two writers for translation. Hilbig, along with his contemporary W.G. Sebald, borrowed liberally from Romantic school, both in style and theme, particularly a focus on the natural world. Setting is a the primary character, for Sifter and Hilbig, the primary driver of the narrative.

In the case of Old Rendering Plant, it’s a soap factory. There, animal carcasses are rendered into tallow, their effluent choking the marshy area where the unnamed narrator plays as a child. The are no named characters in book at all, apart from the plant itself, Germania II, which carries an unmistakably fascist connotations. When people from surrounding area go missing, suspicions are cast on the plant workers, who form their own ostracized circle among the other industrial laborers. This might seem like a gruesome but relatively straightforward political allegory, but Hilbig transforms the old rendering plant into a site of planetary rather the local evil.

It…this essence…had come over a crust of earth, which was permeated, maybe deep down into unexplored regions, with the substance of its exterminated species. Stratum after stratum, all the species’ decay had covered the earth. Particle by particle, extinct matter had seeped through the planet’s porous mantel to infiltrate the fire-born rock; for eons of past life, death and putrefaction, atom by atom, had claimed Gaea, the mother, and all that sprang from her bosom was saturated with the urine of dead rats.

Apart from the ironic reference to Gaea, I might have thought the passage was by Lovecraft himself, in a rare burst of controlled (or well-edited) writing. The two authors converge modally, on similar moods and narrative perspectives. Taking literary history into account, this makes sense. German writers of the Romantic era (Kleist, Hoffmann, and Jean Paul, among others) were keen observers of natural science and enthusiastically incorporated its findings into their tales. Through Poe and through popular translations, their stylistic and natural philosophical innovations came to Britain and America, where they were adapted and adopted into the popular literature, then further developed by Lovecraft and his descendants.

With his vivid, sinister landscapes and ornate syntax Hilbig also partakes in that tradition. The influence of Kleist and Stifter are particularly vivid when reading his prose in German. There are English language influences as well; Explicit allusions to Joyce feature prominently. But I wouldn’t be surprised if Hilbig also read Lovecraft. Then again, explicit influence isn’t necessary for such parallels. They share the same mutant heritage.