On Calenders

Sculpting time with pictures of cute animals

News and Sundry

I’d like to thank leonor grave for becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter. Subscriptions help immensely with the costs of running a small press, which, even on a very DIY basis, are not nothing, not inconsiderable. In case you missed it, I released a pamphlet of Kleist translations through Paradise Editions. Newsletter subscriptions also enable me to write on volunteer basis for excellent publications. In that capacity, I’d also like direct people once again to The Graveyard Review, edited by leonor and Stacia Phalen, where I have a piece about the Woodlands Cemetery in West Philadelphia.

Calendars

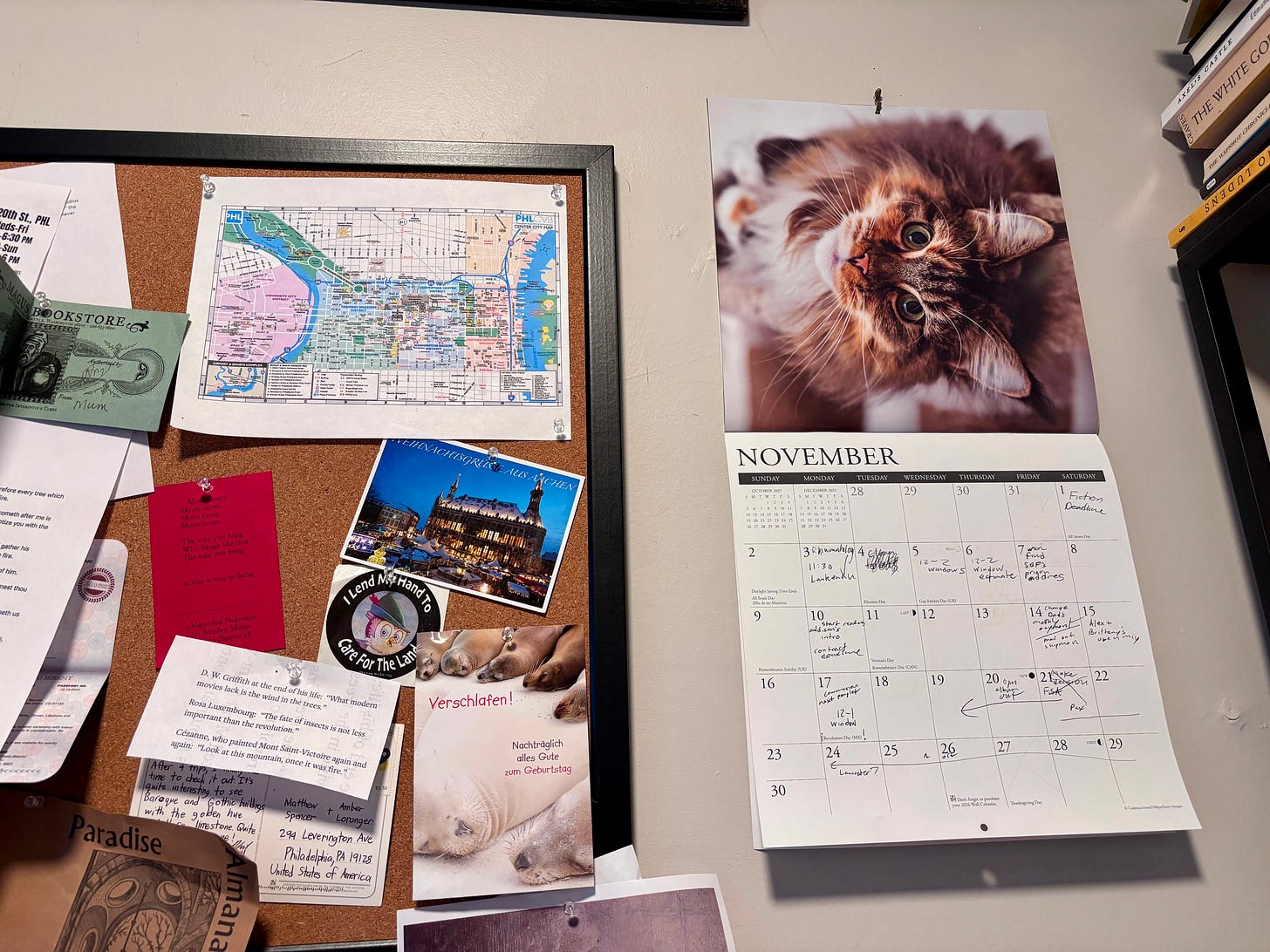

It’s November, firmly so, and time for replacing the old wall calendar. I have a great respect for calendars as a physical medium. Johann Peter Hebel wrote some of my favorite narrative prose in German for them, appending tales like an “An Unexpected Reunion” and “A Peculiar Ghost Story” to the usual index of days and months, tales about everyday people for everyday people—farmers, miners, butchers, bakers, and the like; Hebel’s subjects were his audience. I really like that.

While calendars aren’t a venue for literary excellence nowadays, they still have nice pictures in them, those that aren’t filled with images generated from “AI” diffusion models, but, then again, that’s a problem in every visual medium, no need to lament the state of calendars in particular. Their makers are just as guilty (or innocent) as anyone else in the media game. The company I usually buy my calendars from is called Red Ember. They’re based out of Reno, Nevada, which for some reason strikes me as apt. Reno strikes me as a calendar making city, don’t ask me why; maybe it’s the proximity to California, which, at least to me, represents the acts of measurement and demarcation more generally.

For 2025, I had a Maine Coon themed calendar, with pictures of that exceptionally fluffy breed posed majestically in front of various plain domestic scenes or even plainer generic backdrops. Though I’ve never kept a fluffy cat, I do have a fondness for them, which I express—insufferably, I know—by the Japanese loanword for fluffy, ふわふわ or “fwa-fwa”. I’m also insufferably amused by footage of Maine Coons in French cat shows, with the announcers doing their best to put an especially French intonation to that very American word: “le Maine Coon”. It’s nice to see images of them, on the TV or tacked to the wall of the home office, without having to vacuum up the bales of stray hair they always leave behind, especially when the weather changes. That extra fluffy breed standard developed naturally, without intensive human intervention, in the cold climate of New England, but it proved just as useful for a semi-feral Maine Coon I knew back in Seattle. He lived in my neighbor Cody’s backyard, never had a proper name as far as I could tell, and burrowed underneath his garden shed during the few odd days of the year when the mild maritime climate would turn snowy. During the summer, great tangles of woolen hair would develop on his flanks, like a stray sheep which, lost in the mountains, can’t be taken in and sheared.

Cody and his wife Donna were elderly, a remnant of when the neighborhood, Fremont, was middle-class and not within walking distance to the offices of several oligarchical tech companies. The couple distrusted me as a renter, that is until I started doing yard work for them, a replacement for the Mormon missionaries who would do the same, on a more irregular basis, though their services seemed worth a conversion to Donna. I also fed the cat when Cody couldn’t, a task which the missionary boys never did, pouring generic kibble into a plastic margarine tub set beside the back porch. I used to worry that the cat was undernourished, since any free-roaming animal could eat its food, or eat it, as could have easily been the case. Foxes and coyotes are not too uncommon in Seattle, even deep into the urban core, such as it is; Fremont is suburban by the standards of the East Coast, dominated by low-slung, detached houses, though their owners (accidental or intentional real-estate millionaires) would vociferously claim otherwise. Me and my wife— then girlfriend—lived in a triplex, the only renters left on our block.

Cody died not too long after I started doing chores for him and Donna, no more than a year or two, and when he died (I can’t remember the cause) then the cat disappeared as well. Donna didn’t like the animal, didn’t want it taken care of on the property, which was hers alone now, and no intervention of mine—setting out food by the back stoop of our triplex or in the alleyway—was enough to summon the cat, that is until around Christmas, during a rare Seattle snowstorm, when the cat crawled underneath a yew tree beside our bedroom window and died there, unnoticed by my wife and I; it was only until about two or three weeks had passed, when the snow partially melted, that we were able to see the cat’s partially decomposed remains among the yew needles and stray trash that our co-tenants threw into the plantings. Donna certainly didn’t want to claim the cat. Having nowhere to bury the cat, I stuffed the body into an extra-strength vinyl contracting bag and sent it out unceremoniously, out of necessity, to the landfill; there was nothing else to do.

For my 2026 calendar, I picked another animal of personal significance: the donkey. Growing up in Glenwood Springs, I would often hear one braying in the morning, usually as I walked to elementary school, that sort of independence still being common, or at least not actively discouraged, not actively prosecuted, in Colorado mountain towns during the 1990s. The donkey lived in a small pasture along the Roaring Fork River. Its hoarse voice (the voice of an angel) would carry over the swift water, and I associate the braying with frost on the grass, the first sprinkling of mountain snow, and the steam that would rise from natural hot springs along the river.

To me, calendars are powerful, almost occult objects—as long as they’re printed. A digital calendar is both wholly mundane and wholly ephemeral. As days go by, the events within them disappear from memory at a rate best described as pre-literate. But with printed calendars, you can organize time rationally but also revisit the past or anticipate the future in a much more concrete way. What was once an anonymous procession of days becomes subject to a more richly lived experience. I will never disrespect a calendar, nor will I disrespect the cute animals, beautiful women, and generic vacation scenes that typically appear on them. I will never reveal how I dispose of used calendars, which is my business alone.

At last, a well written article on Substack (but for that one object-pronoun mishap). You actually got this cynic to feel something about a fucking cat.

Omg this was so endearing