No Time Is Timely

On the early poetry of Robert Walser

Late last month, I attended two readings in Brooklyn, both at Unnamable Books. The first featured the work of Fernando Pessoa, organized by Leonor Grave as part of her Disquiet Radio series, a freeform program on the life and work of the great Portuguese modernist poet. The second reading was organized by my publisher, Sublunary Editions, for the launch of My Heart Has So Many Flaws, a collection of early poems by the Swiss writer Robert Walser, translated by Kristofor Minta.

I first got to know Kristofor through his translations of Rilke, then from A Perfectly Ruined Solitude, a fantastic collection of his original poetry, which merits a full post in itself. Like me, he got into translation as a kind of self-directed literary study, the figure of W.S. Merwin being an inspiration to us both in that regard. I firmly believe that interest in composition for its own sake is the most important quality in a translation, not fidelity to the text (however that’s measured). I’m glad that Kristofor is in this camp.

Selection of material, provided you have a choice, is a crucial aspect of any translation project, and My Heart Has So Many Flaws is well-executed in that regard, adding depth to a writer who has become something of a caricature in conventional literary history. Walser is perhaps best known for his short prose, for the essays and stories that appeared in German newspapers and magazines. He also gained notoriety through the tragic circumstances of his later life. After a period of youthful success, Walser became more withdrawn and mentally unstable in middle age. He found it increasingly difficult to get commissions or to be paid adequately for them. As the reading public deserted him and poverty encroached, he began composing work privately, for the pure joy of writing itself, in a microscopic script on loose bits of paper. A full story might be contained on a postcard. These writings, many of them unpublished and indeed undeciphered until well after Walser’s death in 1956, led to a steady revival of interest in a writer who had fallen into almost total obscurity.

But the poems in My Heart Has So Many Flaws were composed during completely different period in Walser’s life, from the turn of the 20th century to the beginning of the First World War, when the poet was young, in his late teens and early twenties, and on the upswing of the career that promised, at least initially, to be very brilliant. He wrote for some of the most prestigious literary outlets in the German-speaking world, sharing bylines with eminences such as Rilke and Tolstoy. This sort of milieu might lead you to think that Walser was not only precocious but also more-or-less fully developed as a poet, but this is not the case and is not, as Kristofor aptly demonstrates, not a bad thing at all. The characteristic irony of Walser, his pose of I-may-or-may-not be serious with all this, had yet to fully crystalize. Instead, we get him at his most openhearted.

Zeit Ich liege hier, ich hab ja Zeit. Ich sinne hier, ich hab ja Zeit. Der Tag ist dunkel, er hat Zeit Mehr Zeit, als ich wünsche. Zeit hab ich zu messen lange Zeit. Nur etwas übersteigt die Zeit Das ist die Sehnsucht, keine Zeit ist zeitig mit der Sehnsucht Zeit. Time I lie here, I have time. I think here, I have plenty of time. The day is dark, it has time, more time than I would wish; Time I can measure, for a long time. The amount grows over time. Only one thing transcends time and that is longing; no time is timely, if it’s a time for longing.

The sentiments here are youthful—only a writer barely out of childhood could be so oppressed by the abundance of time given him—but they aren’t juvenilia. “No time/is timely, if it’s time for longing,” holds good, as far as my experience goes, at any point in life. Desire might be palliated with age but it can never quite be done away with, and there is always regret to deal with.

Kristofor skillfully uses added variation to tease out the vernacular character of the German. “Ich hab ja Zeit,” could equally mean both “I have time,” and the more emphatic, “I have plenty of time.” For my part, I used to be quite doctrinaire about additions in translation work, in my own and in the work of others. If a phrase was repeated exactly from one line to the next then it would be repeated exactly. As I’ve gained more experience and tackled more poetry, those scruples have fallen away. What matters is not an individual word its individual position, but the rhythm and the tone those convey, in this case the casual but deep melancholy of a lovesick young man.

Walser made a name for himself writing in the German cities of Munich and Berlin, but at heart he remained a small-town kid from Switzerland, and it is his nature scenes that resonate the most with me, growing up as I did in the mountains of Colorado and Washington State. Walser is a poet of springtime, of verdure and regeneration, fitting for somebody born in April, but this is complicated by an equal love for winter, which at high elevations can persist well after the equinox. Easter snowfall is not uncommon in both the Alps and the Rockies. The sun, rising higher each day, is nevertheless shaded by forests, canyons, and mountain peaks.

Am Fenster (I) Zum Fenster sehe ich hinaus, es ist so schön hinaus, es ist nicht viel. Es ist ein wenig Schnee, auf den es regnet jetzt. Es ist ein schleichend Grün, das in ein Dunkel schleicht. Das Dunkel ist die Nacht, die bald in aller Welt, auf allem Schnee wird sein. Hin schleicht sich freundlich Grün ins Dunkel, auch wie schön. Am Fenster sehe ich’s. At the Window (I) I gaze out the window, it’s so lovely. Out there, it’s nothing much. There’s a little snow getting rained on now. There’s a creeping green that creeps into darkness. That darkness is the night, soon to be upon all that snow upon all the green in the whole world. Down creeps the friendly green into the dark—oh how beautiful. At the window, I see it.

Again, Kristofor uses some spare and tasteful additions to bring out the poem's casual lyricism, in this case an added dash in the penultimate line. The original rhythm is preserved, at least how I read it, but a comma wouldn’t be enough, not in English, to bring out that sad delighted pause before “Oh how beautiful”. This new punctuation, no small matter, accomplishes a difficult task.

If biography counts as much as the work itself, then Walser’s posthumous revival (what a phrase) largely rests the last few decades of his life, which he spent institutionalized in various asylums. He committed himself voluntarily and was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, though this is now disputed. He received visitors and was, so he claimed, generally contented with his lot as an institutionalized person, refusing to leave when the option was presented to him.

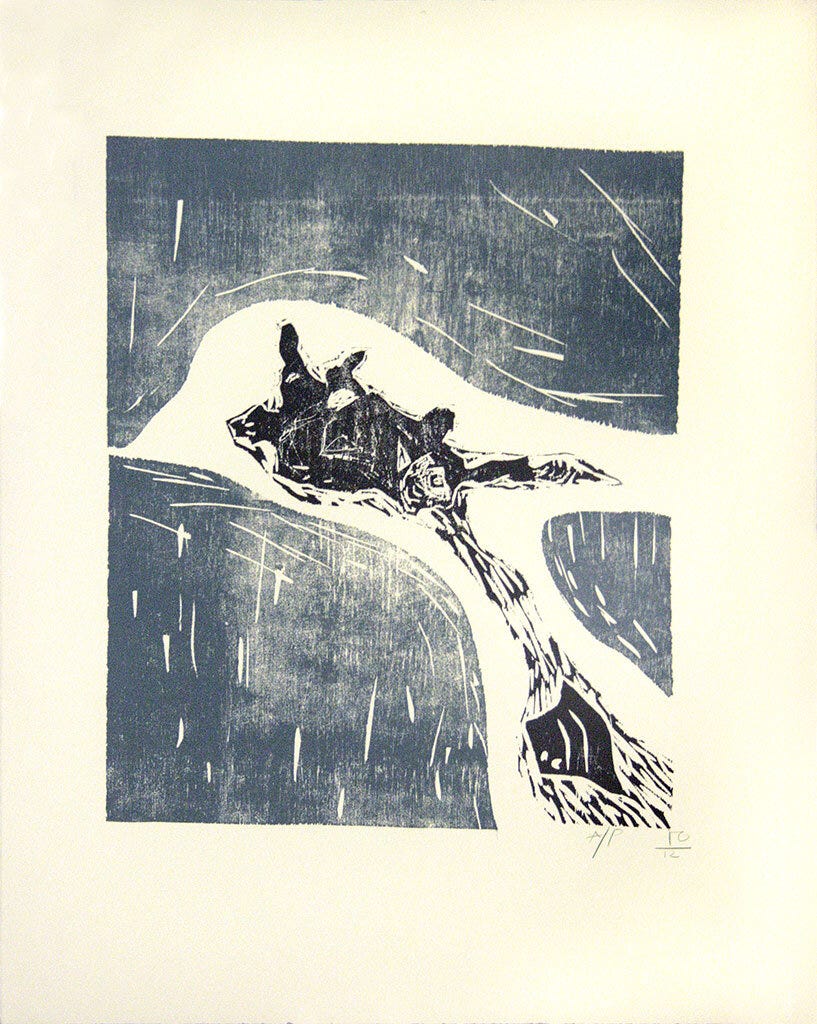

Walser also continued with long rambles through the countryside, a custom he practiced all his life and served as source material for some of his best work. It was on one of these walks that he died of a heart attack, in December 1956. A photograph of him lying dead in the snow has become, arguably, more famous than any poem or short story of his. The image has been depicted by a number of visual artists, among them the English musician and painter Billy Childish.

Though his early poems are written during an optimistic period in Walser’s life, their natural setting, attended by natural dangers, can give them a sinister overtone in light of what we know.

Seht Ihr Seht ihr mich über Wiesen ziehen, die steif und tot vom Nebel sind? Ich habe Sehnsucht nach dem Heim, dem Heim, noch nie von mir erreicht und auch von einer Hoffnung nicht berührt, daß ich est jemals kann. Nach solchem Heim, noch nie berührt trag ich die Sehnsucht, nimmermehr stirbt sie, wie jene Weise stirbt, die steif und tot vom Nebel ist. Seht ihr mich angstvoll drüber ziehen? Do You See? Do you see me, crossing meadows stiff and dead from frost? I yearn for home, the home I’ve yet to find, untouched even by the hope I ever will. For such a home, never met, I nurse a longing, never to wither, as this meadow does, stiff and dead from frost. Do you see me crossing it, full of dread?

It would be a mistake to read prophecy in these lines, however apt they might be for Walser’s death. They also express the normal foreboding one might feel in an empty inhospitable place, when the outcome of some taxing journey, especially by foot, is uncertain. That the poem intimates disaster is just as much a function of its composition as it is of later biography. Plenty of people who feel the sublime, the vast majority of them, die comfortably in bed.

As he notes in his afterward, Kristofor was initially skeptical of Walser. There was something in his ironic attitude that didn’t connect. This wasn’t helped by early translators, such as Christopher Middleton, who favored the later, more urbane side of his work. And while I’ve always had a great readerly affection for Walser, I can see where Kristopher’s argument is coming from. There is often a reflexive, even self-amused quality that can be somewhat off-putting when full sincerity is on order. But here, in these poems, we find Walser unguarded, and for all the yearning and morbid premonitions he is a delightful poet, “an antidote to despair.”