From the Shoproom Floor

On being absentminded and maintaining a business

Phoretics, Israel Bonilla’s chapbook, will be published imminently through Paradise Editions. There’s still a chance to get a copy, but our initial run of 50 is almost sold out. Once that happens, I’ll begin working on an unlimited paperback edition. For those dear readers who have already purchased a copy, yours is on the way and should arrive shortly. The production of Phoretics has been quite stressful, enough to make it obvious that it should have been a short, conventionally-bound paperback from the start, rather than a hand-assembled book arts project. Although I do have some ideas for future pamphlets and other ephemera, I’ll be shifting my focus away from them. That said, I’m still incorrigible when it comes to taking on new projects, so I won’t promise not to undertake anything like this in the future.

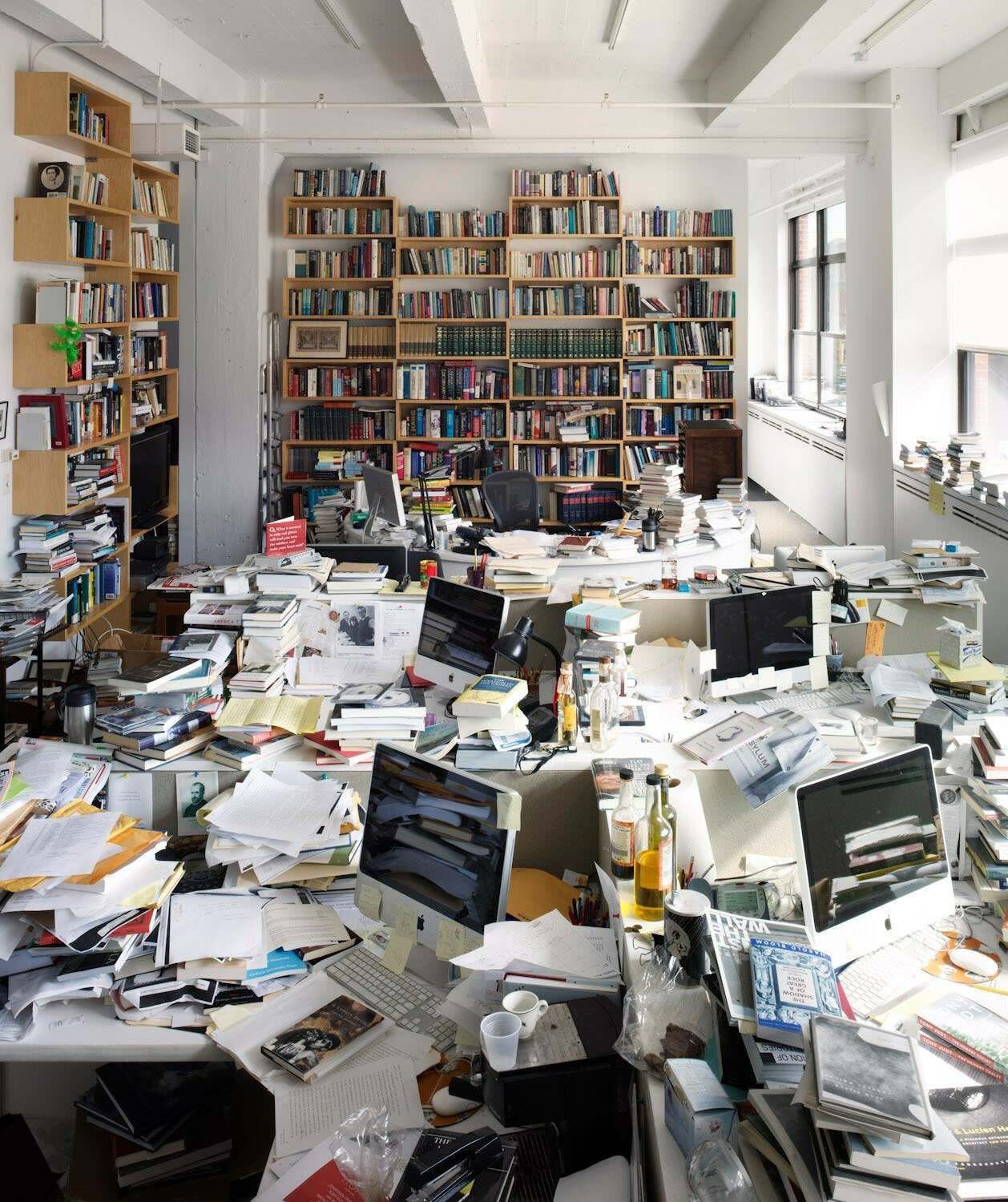

Assembling Phoretics has got me thinking about my need to have a clean and orderly working space. It’s a conventional idea, but one that runs contrary to the romantic notion that artists and writers benefit from a certain level of chaos in their lives. I’m thinking most especially of certain photographs of Lucian Freud’s studio, with its sublime heaps of material—paints, paper, canvas, and so on—piled on the floors and against the walls. Visitors remarked that he never put the lids and caps back on to anything.

A blogger might be tempted to draw some broad kind of generalization about how an artist’s working space is a reflection of their fundamental temperament and the ideas that they convey through their art. That seems true enough, but it is also equally as accurate, and much more useful, to think of Freud as a wealthy, world-famous painter who had studio and gallery assistants readily available to him. Their job was to pluck saleable items from the mess. The vast majority of artists, then and now, did not have that level of support.

I’m chaotic, do not do well in chaos, and resent its presence around me. I constantly lose track of the most common household objects. I will forget that I put a water glass on a table, in reach of the cats, the moment I put it on the table. The term “absentmindedness”, with its twee, professorial associations, fails to get at how enervating that state is, especially since it’s claimed by so many otherwise attentive and organized people.

It’s also been my experience that these so-called absentminded people will often become agitated, annoyed, even outright hostile when faced with real absentmindedness. I remember an elementary school teacher dumping out my desk because there was simply “no way” I could have lost my art supplies between the beginning and middle of class. This kind of interaction has repeated itself with varying degrees of intensity throughout my life.

The big exception to this personal chaos has been with books I sell online. I’ve run office mailrooms in the past and done stocking for retail, and while I have never been the quickest, I’m still decent at organizing goods for sale. I’d be out of my depth managing a supermarket or a restaurant, sure, but the baseline in the book trade is much more forgiving. I’m thinking of the cluttered but rational system that governs the best used bookstores—Magus in Seattle or Mother Foucault’s in Portland, for instance—where an interested customer can pick out something interesting from the bibliographic heaps that surround them. But new books require more tender treatment, so I’ll keep sweeping and vacuuming and reshelving my merchandise. It might do me some good.