Enlifening Planet: On A Cypresse Grove

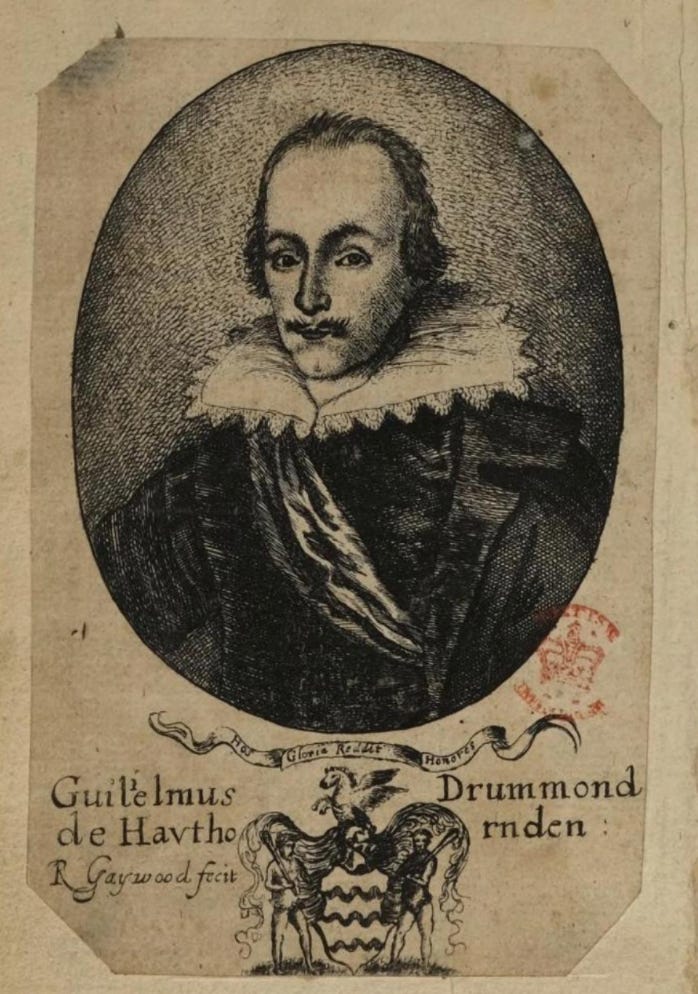

The view from the sickbed can be quite consoling, provided accounts are in order, the rents paying, not payable. Through old glass, castle windows, dull transparent gray, a gorge can be seen meandering, moon and planets resolved at dusk. In such environs, during a bout of severe illness, William Drummond of Hawthornden, laird and poet, wrote A Cypresse Grove, an essay of about 50 pages, recently reprinted by Empyrean Editions. Its genre, the meditation on mortality, was nothing new, Ecclesiastes being an obvious forerunner. But Drummond lived in the 17th century, when physics and astronomy were rapidly developing, aided by new instruments, the refracting telescope foremost, high technology at the time.

“The Earth is found to move,” Drummond writes, “and is no more the Center of the Universe, is turned into a Magnes; Starres are not fixed, but swimme in the etheriall spaces, Comets are mounted above the Planetes, some affirm there is an other world of men and sensitive creatures, with Cities and Towers of the Moone, the Sunne is lost, for it is but a cleft in the lower heavens.” Antiquity grants a suppleness of style. With Drummond, the immense scale of the universe, affirmed by billions of dollars in research expenditure yearly, becomes a perennial subject rather than a topical one. Simple clause follows simple clause but in unexpected ways. English had yet to be fixed by the dictionary and the classroom. But a handheld instrument, its lenses coarsely ground, is sufficient to gain cosmic perspective.

The time after us is vast, endless perhaps, but we are no less dwarfed by the time before. This is not usually a source of distress. Vladimir Nabokov provides a notable exception at the beginning of his memoir, Speak Memory: “I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged—the same house, the same people—and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence.” More than seventy years have passed since Nabokov wrote the passage, the young chronophobiac having likely moved, like the novelist himself, into that state of lateral equilibrium.

Drummond made a similar observation a few hundred years earlier: “If thou dost complaine that there shall bee a time in which thou shalt not bee, why dost thou not too grieve that there was a time in which thou wast not? and so that thou art not as old, as that Enlifening Planet of Time? for not to have beene a thousand years before this moment, is as much to bee deplored, as not to be a thousand after it, the effect of them being one.” The demand is never—almost never—made for our years to stretch backward as well as forward, though this would provide the same degree of enlifenment, as Drummond puts it. The years preceding our birth weigh lightly on us. It would be burdensome to add a dozen, never mind the lifespan of a whole planet, even by James Ussher’s reckoning.

But philosophy can never offer consolation proportionate to its claims. If it could, then Ecclesiastes would have been the last word on the subject. There is a certain vanity in striking out against certain vanities. A writer could have endless employment, provided the job was well paying. Better to have some independent means. Death is impartial, but equanimity is easier if your view encompasses hereditary lands and tenants.