Book of Hours I: Brimstone Flowers by Jean Paul

"I do not know what it is," Walt said, "but I find no true poem."

I’m in between translating prose books at the moment but not quite ready to quit Jean Paul, so I thought I would start an irregular series of shorter translations of him—irregular because I have a few book proposals under consideration and any one of them could take over my life for the next few months.

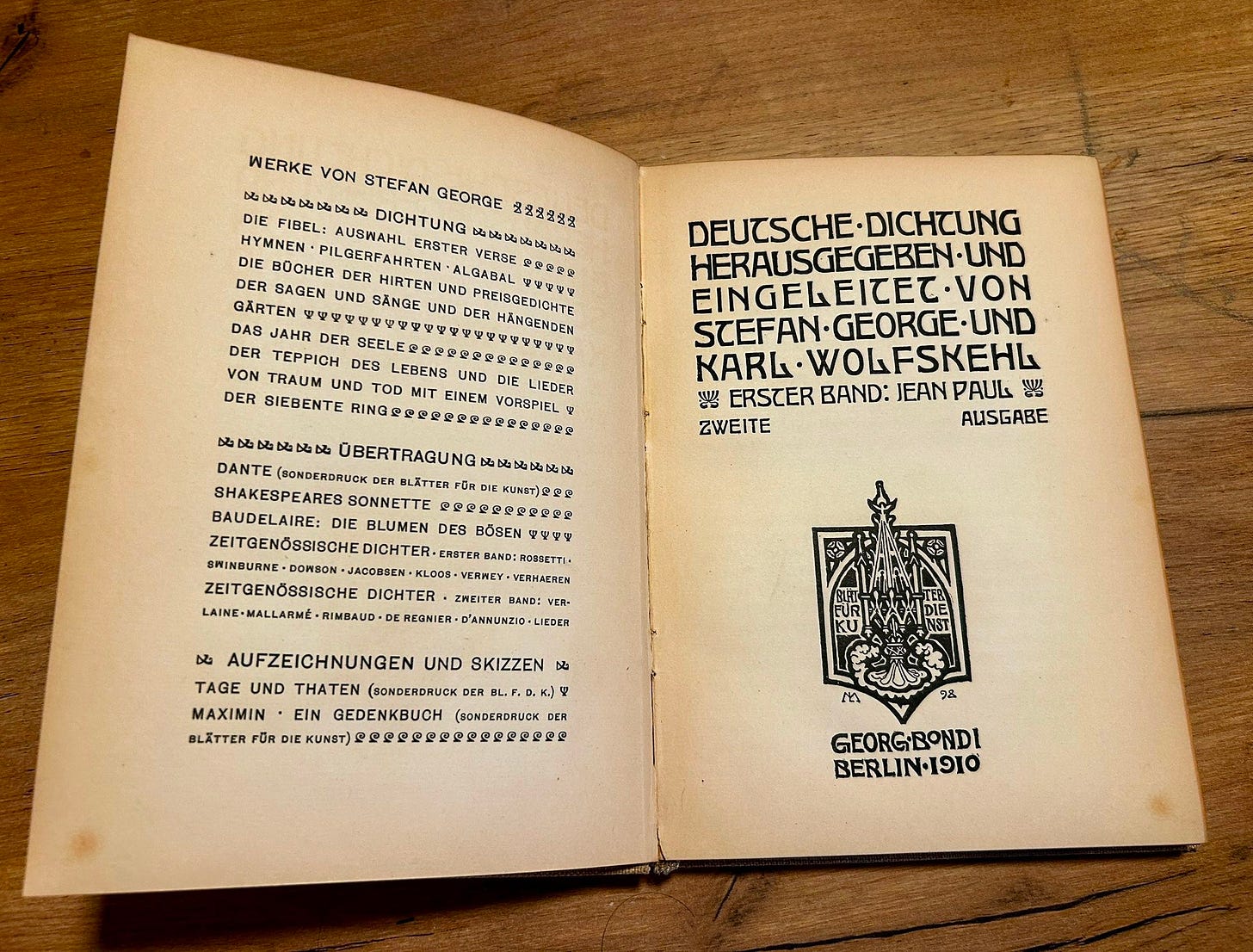

The J.P. selections come from a 1910 anthology edited by the eminent symbolist poet Stefan George and the German-Jewish writer and translator Karl Wolfskehl. The book covers a wide range of material, mostly passages from famous novels like Titan and Hesperus, lesser-known works such as Biographical Recreations, along with other, even more obscure odds and ends.

The pieces in the anthology tend to emphasize J.P.'s dreamlike and idyllic qualities, rather than his more ribald or satirical moods, which, along with their brevity, makes them much easier to translate than any of the previous work of J.P.’s. I’ve done. The anthology, in its first edition, was originally titled The Book of Hours, which makes for a much more evocative title than the one for my edition: German Literature: Jean Paul. I’ve decided to title this series after the first edition.

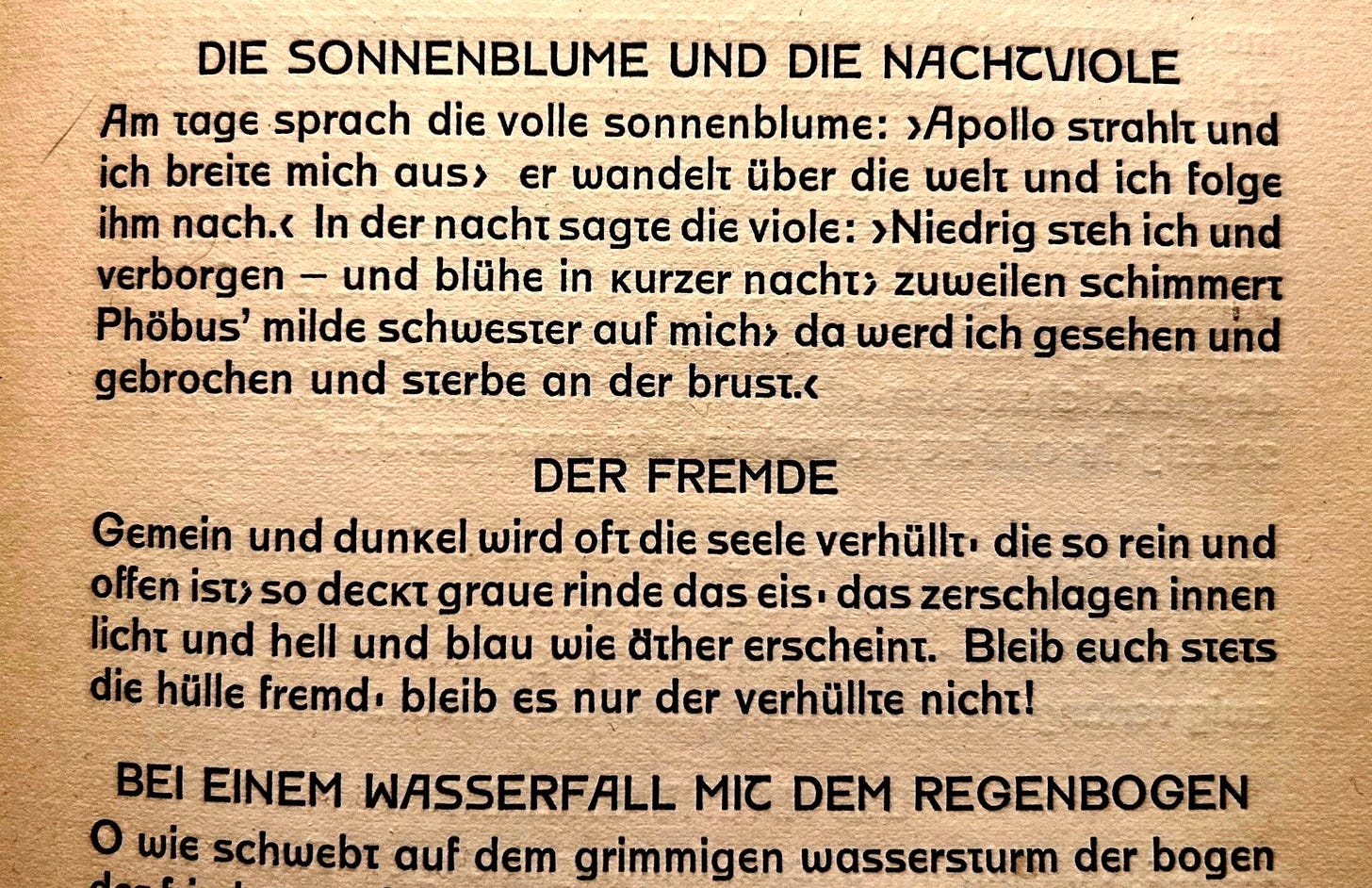

The book itself is a beautiful object, befitting Stefan George’s editorial involvement, and designed in the German Art-Nouveau style called Jugendstil. The body text is quite modern, even futuristic (or retro-futuristic) looking; its angular, sans-serif font reminds me of science-fiction posters from the 70s or 80s, especially the punctuation, which is wild considering that Fraktur, the Germanic blackletter script, was still quite commonly used in 1910. It might not meet contemporary standards of legibility, but compared to its contemporaries, the book is quite easy to read.

The first of my translations come from a series of short prose pieces at the back of the anthology—“Streckverse” as Jean Paul called them. Rendering the word into English is difficult. It means literally, “stretch-” or “extended-” or maybe “duration-verse”. George and Wolfskehl selected most of these Streckverse from J.P.’s unfinished novel Walt and Wult, where a helpful definition of the term is offered:

“What is it?” asked Knoll, drinking. “Herr Graf,” said the schoolmaster, and led the count aside; “Herr Graf, it is, in fact, a new discovery of the young candidate's, my pupil, sir! He makes poems after a free meter entirely his own, consisting of one verse only, free from rhyme, which he prolongs at his own pleasure, and calls a Streckvers; and he has faith in their success. What he calls Streckverse I call polymetres.”

Contra J.P. (and like Walt) I don’t think of these pieces as verse, but more like anecdotes or feuilleton, very similar to what Heinrich von Kleist was writing in his newspaper, the Berliner Abendblätter. At any rate, good material for my own newsletter. The title “Brimstone Flowers” comes from a chapter in Walt and Wult in which Wult, the fictive composer of the Streckverse, has his compositions read to a puzzled audience. Like George and Wolfskehl, I’ve removed the interstitial dialog between the pieces, except for the sentence quoted above in this post’s subtitle.

I’m putting up the first few passages for free, but paywalling the rest. As I said, I’m between book contracts and, in the absence of a day job, have to rattle my mendicant jar somewhere. If you don’t want to commit to a subscription, I will include a mini-broadsheet (read: printout) with some of these “extended verses” for orders made at my press, Paradise Editions.

The Reflection of Vesuvius in the Sea

“See how the flames fly up, drowned among the stars! how the red current rolls heavy, round the mountain of the deep, devouring fair gardens along its path. But we, unharmed, glide upon cool flames, our image smiling back, within the burning waves.” So the seaman spoke, glad of heart, though he looked back pensively at the raging mountain. And I said, “See how the muse so lightly carries, reflected in her deathless mirror, the heavy sorrows of the earth; the unfortunate gaze therein, and smile back at their pain.”

The Sunflower and the Violet

By day, the sunflower said: “Apollo shines and I spread myself. He walks over the world and I follow him.” At night, the violet said: “Low I stand and hidden—and bloom in brief darkness; sometimes Phoebus’ gentle sister shines on me; then I am seen, I am broken, and my heart perishes.”